Guru Yoga

“The logical mind seems interesting, but it is the seed of confusion.”

— Patrul Rinpoche

~~~~~~~~~~

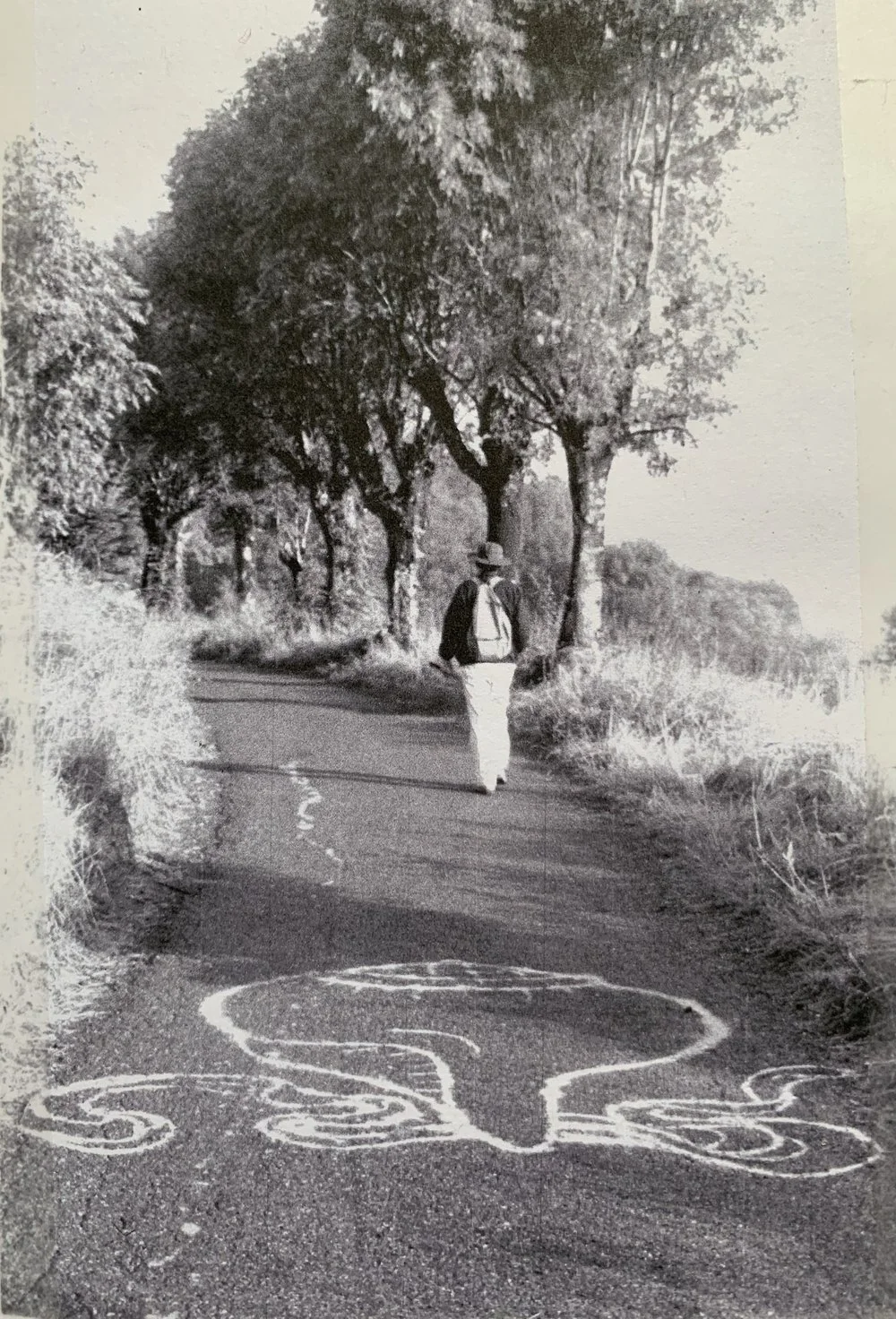

Sitting in the view, Lerab Ling 3-month retreat, France 1992 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

~~~~~~~~~~

Dharma is the Sanskrit word for “truth.”

The dharma, or way of being that accords with the teachings of the Buddha, can also be defined as the study of phenomena and the way we perceive or hold phenomena. The Buddhist teachings are rich, vast, and profound—and they are challenging to digest. To nurture an experiential understanding of the teachings, it’s ideal if one can reside for a while in a retreat environment, free from the lure and obligations of worldly affairs.

After the magical, awesome 1992 three-month retreat at Lerab Ling, I confessed to my friend Owen my fear that I would become a nun.

“That’s a lot of nunsense!” Owen replied. Owen rarely indulged in puns, so his spontaneous wordplay spooked me into sensing even more strongly that it might happen. I knew nothing about the ways of monastic life, and I didn’t envision myself sequestered in a nunnery. Yet the so-called perks of samsara no longer interested me. I wanted to be finished with the samsaric cycle of birth, old age, sickness and death, which is rife with suffering because of habitual clinging to a false sense of self. I wished to no longer be propelled by negative emotions and the karmic force of previous actions. Back in 1985, I felt I had managed to cheat death. Now I was inspired to explore the Buddhist view of death to quell my fear of it.

My appetite to live in the light of wisdom was strong, yet it was easy enough to put ordination out of mind. Nothing in my Jewish upbringing endorsed such a step and no one among my artist friends had cause to even think let alone suggest that I should adopt a monastic lifestyle. Nevertheless, I knew I needed to simplify my life one way or another to allow for uninterrupted study and practice.

Auspicious sign of the conch on road entering Lerab Ling, 1992 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Interior view of shrine tent. Drawing by N. L. Drolma (watercolor, ink, 4” x 7”)

The grace of a butterfly, Lerab Ling retreat center, France, Summer 1992 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

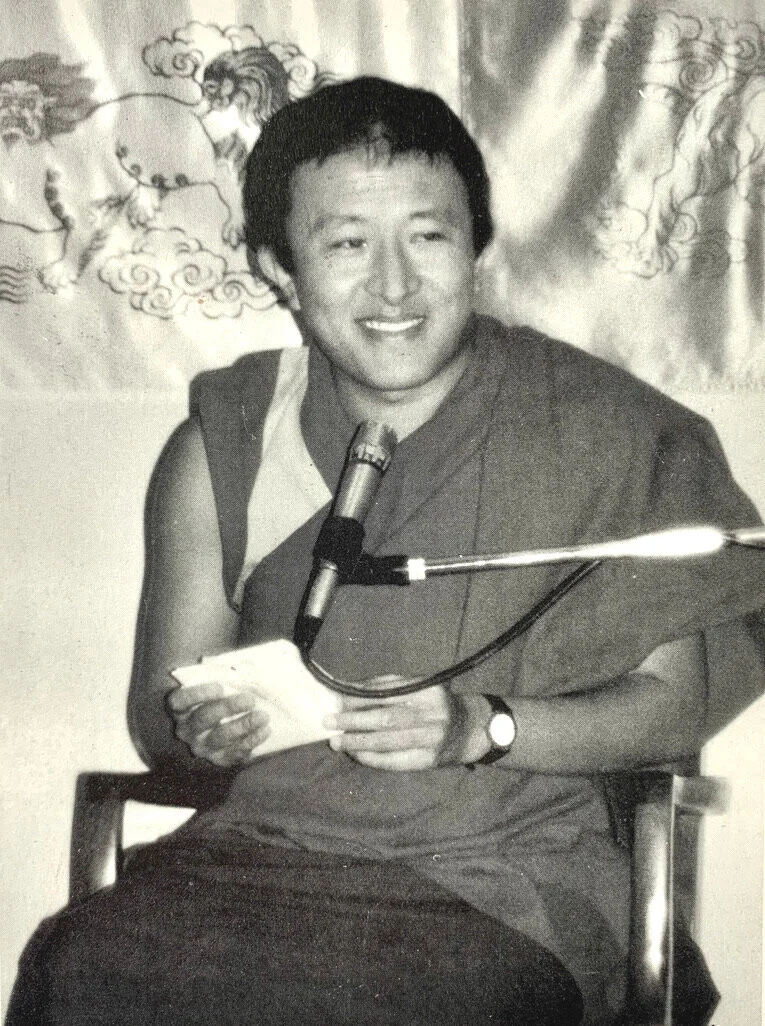

Sogyal Rinpoche’s teachings that summer unfolded a magic carpet of Buddhist practices. When I returned home from Lerab Ling in the fall of 1992, several sangha members noticed how differently I sat on my cushion: my posture was “inspiring,” “so straight!” and “confident.” One sangha brother said bluntly, “You’re just much nicer to be with than before.” The teachings had exposed my timid heart and helped me to recognize self-deception, and how to cut through it. The profound oral instructions introduced me to what was beyond imagining: the clear, pristine, unfabricated nature of mind, which is the nature of all beings and of everything. Certain there was no such “thing” as mind to find, I prayed to strengthen and stabilize recognition of pure awareness. Guru Yoga—uniting one’s mind with the mind of the master—was a powerful support for doing just that.

◊

Just what does that entail, uniting one’s mind with the mind of the master? How does one do that? Is this safe for me to do? Why should I trust someone else with my mind? In this practice, what is meant by “mind”? Those were some of my thoughts on first hearing about Guru Yoga. I was eager to know more and sought out teachings. The more I listened to teachings and the more I read, the more inspired I was to enter into the practice and develop an understanding that was not based on book learning alone.

Whether I was physically on the meditation cushion or out and about running errands, I found myself nourished by Guru Yoga; it revealed the space that’s always present, even in situations where there seems to be none. Recitation of the Vajra Guru mantra or simply visualizing Rinpoche in my heart put wings on my feet. I was feeling light and happy.

The nuances of the teacher-student relationship in Vajrayana were becoming clearer to me too. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, who visited and taught at Lerab Ling during the '92 three-month retreat, has stated flat out that teacher and student can enter into a dance together and play lots of games. What a student wants may not be what a student needs, and if the teacher is not accomplished or lacks confidence, he or she may not have the courage to give the appropriate teachings. I found that I had to bring to this uncommon friendship not only a thirst for wisdom but the willingness to be patient and trust, especially when I was not in the mood for either.

In my initial wanderings through Dharma wonderland, I didn’t understand what was meant by the guru as a “universal principle.” I did not care to hear that Sogyal Rinpoche could be sleeping quite peacefully in Paris and also be there for me at the moment of my death. For this girl, the universality of the guru was religious talk and too abstract.

Sogyal Rinpoche with children of the Rigpa sangha at Lerab Ling, France, 1992 or ‘93 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

What helped me to approach this broad view of the guru was the traditional and oft-repeated advice not to rely on the personality of the teacher, but on the teacher’s instruction. I found Sogyal Rinpoche’s personality to be quixotic and at times unnerving. Rinpoche said of himself in public that he was an ordinary man, but my circle of friends and I thought otherwise. Rinpoche’s teachings on how to diffuse negativity and cultivate a sane, generous view of ourselves and others were blunt, provocative, and often eloquent.

Guru Yoga in particular was taught as a compassionate, skillful means to access our innate purity of perception. It is said by the great masters of the past that the greatest blessing comes from thinking of one’s teacher as a human embodiment or personification of inconceivable wisdom light—and that is how Sogyal Rinpoche appeared to me one night during a powerful teaching. In that same momentary shift in perception, my fellow retreatants manifested as figures of rainbow light too.

Of course, this may sound more than a bit “woo-woo” if you have been educated to disavow accounts of phenomena that transcend mundane perception. Longtime dharma practitioners might also wince at my writing here and wonder why I am speaking of this, or of any experiences, inasmuch as secrecy is the norm and it is understood that such talk can invite obstacles and ridicule and dissipate the power of one’s practice. However, the Buddhist teachings do say that well timed, judicious candor is appropriate if the intention is solely to benefit others.

Postcard announcing Lojong teachings by Dzongsar Khyentse (based upon Dilgo Khyentse’s book Enlightened Courage), Karme Choling, Vermont

Many westerners, especially those who are new to the buddhadharma, may be encouraged by hearing from a fellow westerner that one needn’t be “special” or born in the Himalayas to open to the vastness of one’s being. To cultivate a good heart, however, is imperative and immeasurably more beneficial than having or getting caught up in luminous visions.

As Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche once advised an audience in California, “Even if Buddha Shakyamuni himself shows up when you are practicing, tell him to buzz off.”