The Fast Lane

~~~~~~~~

“ ‘Who are you?’ said the Caterpillar... Alice replied, rather shyly, ‘I—hardly know, Sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.’ ”

— Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

~~~~~~~~

I watched my father search for the Monster under my bed before giving me his usual big, big hug and kiss and tucking me in for the night. He declared there was no Monster. But I lay awake unconvinced. If the Monster wasn’t under the bed waiting to grab me by my ankles, maybe he was hiding in the walls or in a corner of the ceiling. I was afraid of the dark, and often stayed up until wee hours of the morning.

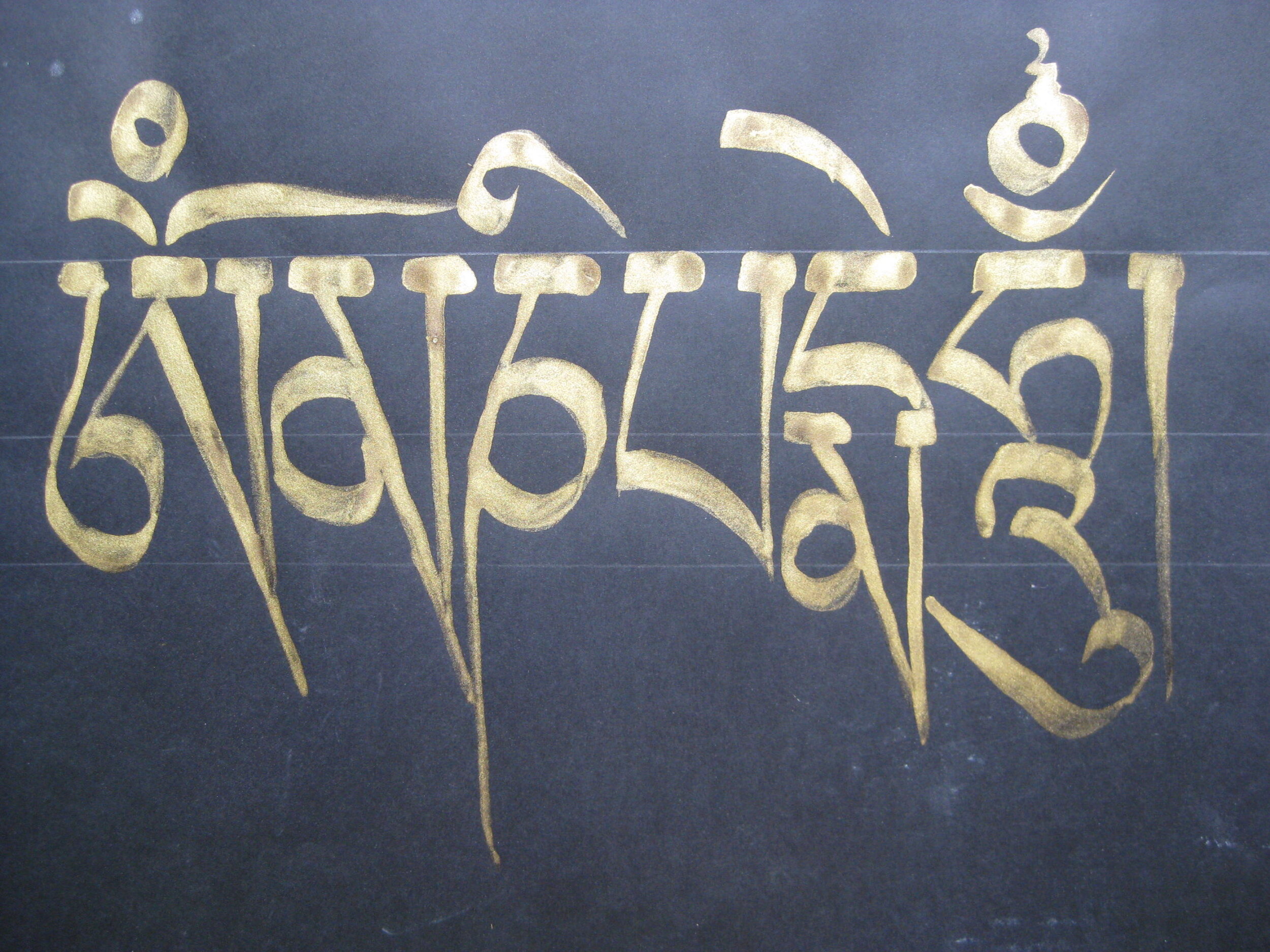

Calligraphy of the mani mantra by Bhakha Tulku Rinpoche, NYC 2008

To induce fatigue, I was instructed to “count sheep.” Though I dutifully complied, it always seemed a silly game. I doubt more than twelve sheep in any one night cleared the fence before my attention shifted to my bedcovers or to the moonlight seeping through the window blinds. Imagine if I had been taught to recite Om Mani Peme Hung instead—compassion in the form of six syllables! I might have made friends with the Monster early on, falling asleep while teaching it how to chant the mantra. There is a saying that children in Tibet learn to say “Mani” before they learn to say “Mommy.” The mantra surely is a more user-friendly method than visualizing the flock.

One night when the sheep were nodding off and I was wide awake—I wondered, ‘Where does the sky begin and where does it end? And what lies beyond it?’ I tried to imagine a cloudless blue sky in the shape of a square. Then, with my eyes closed I waited, extending the suspense of the moment before allowing myself a peek at the mysterious something that would materialize beyond the square sky. What a disappointment! There was only more space, and it was just as blue as the sky. But what if the sky was circular? What might I find surrounding it? After conjuring up the circle of the sky in my mind’s eye, space of course was all I found. So, I asked the sky itself to take on its true shape. With eyes alternately open and closed, I waited for the answer. Perhaps I fell asleep that night with one eye half-open.

◊

When a friend gifted me a copy of Suzuki Roshi’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, I was a 30-something artist living in Greenwich Village. Inspired to continually reflect on its lean, elegant contents, I carried the book with me everywhere. Subsequently, thanks to the maverick ways of Tibetan Buddhist masters, I slipped down the rabbit hole and found myself off the beaten path, seduced by the dharma. Is it any wonder that a little girl who tried to map the sky became an adult keen to explore the mind’s boundless nature?

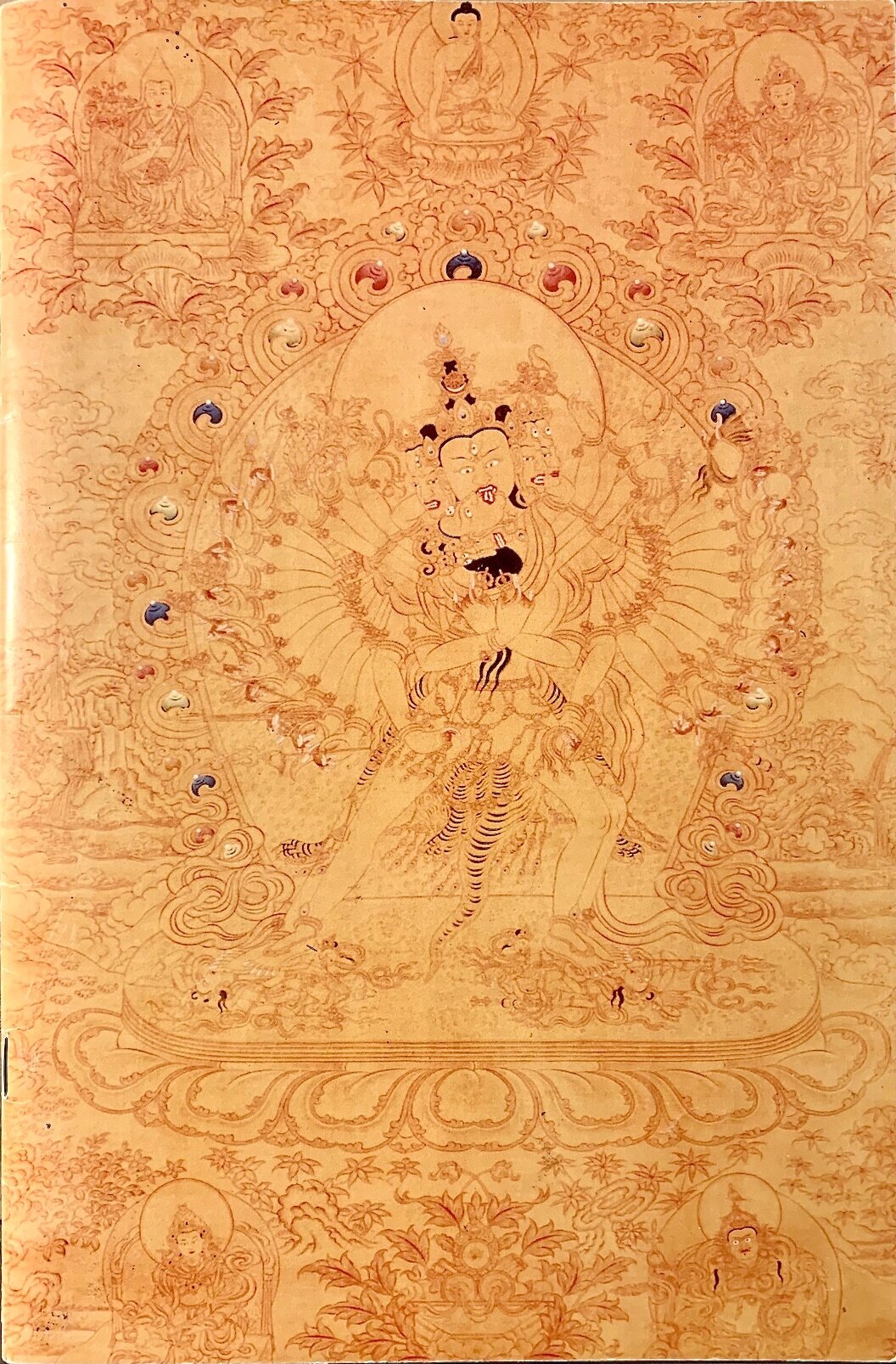

HH the 14th Dalai Lama was conferring the 1991 Kalachakra Initiation for World Peace and eminent lamas from all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism were offering teachings on the nature of mind. New York City’s usual jostle and heated tempo had dissolved as if by magic—everything seemed much less pressing. The amphitheater of Madison Square Garden and local venues had been transformed into a Himalayan hidden land, complete with the extended wail of Tibetan horns heralding the buddhadharma; the long, low-sounding notes of the dungchen released in me a shudder and warmth akin to the first time I tasted cognac. I was enthralled.

Cover art to the program notes for the Kalachakra Initiation and teachings on nature of mind bestowed by HH the Dalai Lama at Madison Square Garden, NYC, Oct 1991

It was during this ten-day Tibetan extravaganza that I wandered into an empowerment. Although I was forty minutes late and had no idea what an empowerment was, I begged the woman stationed by the door to let me in. There was recitation of Tibetan text and ritualistic bell-ringing. Red strings (protection cords) were distributed among the audience and were to be worn around the neck or wrist for three days. We now had permission and were “empowered” to do the practice of Lama Gongdu (unifying one’s mind with the wisdom mind of the guru). The revered master who bestowed the empowerment was Trulshik Rinpoche (late tutor to HH the Dalai Lama). Clueless as to what actually transpired because of my extreme tardiness, I was happy to be fully present for the teaching that Trulshik Rinpoche then offered— “Dzogchen and the Nine Yanas”—a comprehensive overview of the Buddhist path, its nine “vehicles” and fruition popularly translated as the “Great Perfection.”

Afterwards, I joined the exceedingly long queue of those in the audience who wished to meet Trulshik Rinpoche face to face. I wondered why he was hitting some people on the head with what appeared to be an odd wooden paddle. There also seemed to be no overt correlation between who got hit and who offered Rinpoche white silk scarves, but I fretted that I didn’t have one.

Clearly, I was a newbie among a throng of three hundred or more Buddhist practitioners. I didn’t know the meaning of “Rinpoche” (Precious One), or even how to pronounce the honorific title (Rin-po-chay). Trulshik Rinpoche’s physical demeanor was eerily elfish and conjured up for me images of leprechauns and pots of gold at the end of a rainbow. After Trulshik Rinpoche whacked me on the head (with what I later came to understand were his prayer books) I thought, I probably needed that.

Trulshik Rinpoche’s profile in the program notes for the Kalachakra Initiation led by HH the Dalai Lama, Madison Square Garden, NYC, Oct 1991

A joyful student declared that it was my good “karma” to be receiving and reveling in these Buddhist teachings. But I knew nothing about blessings or ritual, and even less about karma. To this naïve New Yorker, karma perhaps was a “fate” best understood by hippies or the Beat poets if not a word coined by California beachcombers.

I was happy beyond reason. I had been magnetized by the presence and the teachings of HH the Dalai Lama, particularly His Holiness’s explanation of bodhicitta―the altruistic intent to bring all beings to the state of enlightenment. It was astounding to learn that an entire culture believed in the basic goodness of all beings and that enlightenment wasn’t poetic fantasy, but a primordial wisdom that could be actualized.

When the Dalai Lama offered refuge and bodhisattva vows, I participated readily. The vows sounded to me like a declaration of unconditional love and not at all an act of religious orthodoxy.

In the Garden theater lobby, I subsequently bumped into the actor/writer Spalding Gray, whose acquaintance I made days earlier during a break in a talk given by H. H. Sakya Trizin, the head of the Sakya School of Tibetan Buddhism.

“Well, didjya, didjya?” Spalding asked me animatedly.

“Did I do what?” Spalding’s playful interrogation itself made me giggle; I needed no punch line. I was a great fan of his scathingly funny autobiographical monologues.

N. L. Drolma’s souvenir playbill, Lincoln Center, NYC 1986

“Didjya take Refuge?”

Ahhh...the Dalai Lama mentioned to his audience that whoever among us chose to take refuge that day need not tell others. Refuge is not something one brags about or flaunts in peoples’ faces. It is a profound vow. Outwardly, it is trust in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha—and in the Lama who introduces us to the Buddhist teachings and how to practice them. Ultimately, it is unshakable trust in one’s own basic wakefulness.

“Well, the Dalai Lama said that it’s no one else’s business... But yes, I did take ‘refuge!’ Did you?

“Nooooo... nooo, no, I did not.” Then Spalding asked me if I knew “Buddha Bob.”

“—Buddha who?”

In that moment, Spalding turned to exchange a quick greeting with Robert Thurman, Je Tsongkapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University. Nodding in the professor’s direction, Spalding said, “He’s known as Buddha Bob, and he’ll be happy to let you sit in on his class lectures.” Bob Thurman offered an energetic “hello” that crested the friendly wave of his hand as he continued on his way.

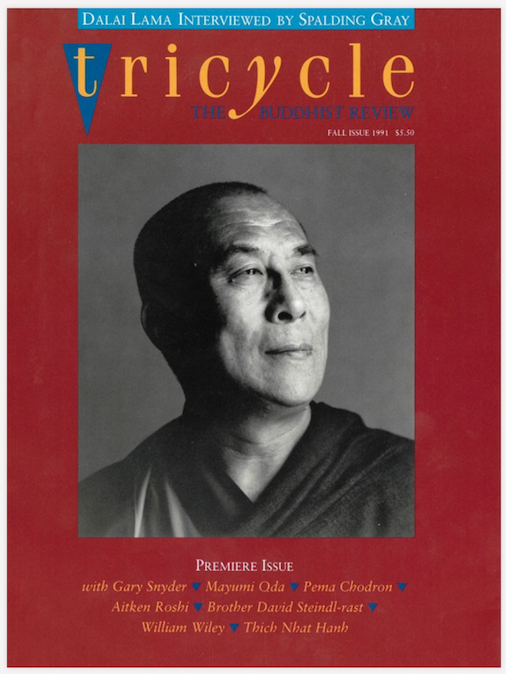

Commemorative edition of Tricycle magazine’s first issue, Fall 1991

Spalding then led me across the lobby to one of the several tables displaying books, magazines, audio tapes and various Tibetan items for sale, and he asked: “Want to see the inaugural issue of America’s first slick Buddhist magazine?” Spalding’s interview with the Dalai Lama was the featured cover story for the new publication, “Tricycle.”

During an intermission break in the Dalai Lama’s teachings that week, I scooted up to the lip of the stage, amazed that no guards were stationed to keep people from getting so close to where His Holiness was seated. I didn’t linger long; His smiling gaze pervaded my body and expanded into the entire space. The day long teachings had short-circuited my mind, and I was higher than the highest-flying kite. But if anyone had predicted that five years later I’d be flying to Nepal to request nun’s vows from Trulshik Rinpoche, I would have replied, “No way — you must be smoking a funny weed.” My encounters with religious groups during childhood and college years had not been all that inspiring. Pious adherents of various sects seemed to incite chauvinism and divisiveness even though they spoke of universal kindness and tolerance. I had little interest in religion.

Sogyal Rinpoche who served as the translator for Trulshik Rinpoche’s teaching also gave a teaching of his own called “Taking to Heart.” He began by reading from his unpublished manuscript that would become the spiritual classic and international best-seller, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. During his talk, Sogyal Rinpoche spoke directly about the nature of mind and when he chanted the Vajra Guru mantra, “Om Ah Hung Vajra Guru Pema Siddhi Hung,” at the sounding of the Sanskrit syllables the hair on my arms bristled and my whole body went piiinnng, not unlike the rush I once felt upon receiving a blood transfusion. I knew nothing about the chant, yet a wild space in my heart recognized itself and for a moment everything came to a full stop. The teaching encapsulated for me profound common sense and pointed to something ineluctable, beyond religion, a strange familiarity beyond the words themselves.

Calligraphic script of the Vajra Guru Mantra (by Drungyik Tsering)

At the end of the session, I was floating on air, stunned with wonder and offered effusive thanks to a couple from California who helped sponsor the event. They were friendly, unassuming folks, and they urged me to speak directly with Sogyal Rinpoche— perhaps sensing how beneficial it would be. But I had no idea what to say to Rinpoche and there was quite a crowd around him, so I walked down the three flights of stairs to the lobby, and with a sigh pushed the revolving doors that exited out onto the sidewalk.

Something then pushed me from within and instead of continuing on outside to the stream of taxis along Seventh Avenue, I turned back to the hotel’s entrance. How could I resume my daily routine as if nothing had happened? I circled twice in the revolving door before re-entering the lobby. Something definitely happened during that teaching, but I was unable to articulate it. I walked slowly up the carpeted staircase. Then, feeling a bit shy and foolish, I walked back down the stairs, only to walk back up yet again. I peeked into the ballroom. The dozens of stiff-backed convention chairs were askew, and the crowd had largely dispersed. Sogyal Rinpoche was still present—he was bidding good-bye to a dharma student and seemed ready to call it a night. I hastened to approach him. My words just tumbled out.

“That heart connection you spoke of ...I felt that with you, and if you weren’t traveling all over the world, I’d study with you.” Then I took a deep breath, and asked: “So, even though you don’t know the nuances of my heart and mind, could you recommend a teacher for me, here in New York?”

Sogyal Rinpoche’s eyes were intense, a fathomless black. He invited me to join him for dinner. His students had arranged an evening out and Rinpoche said we would have more time to talk then.

Seven months later, in mid-May after my first retreat with Sogyal Rinpoche on the West Coast, I was hurriedly making preparations to attend a three-month summer retreat to be led by Rinpoche in the south of France. I forfeited the lease on my artist studio to defray some of the expenses for my summer overseas. This was no minor move. Art was my raison d’etre, yet here I was letting go of great workspace, whose like and low rent I’d be hard-pressed to find again.

One of Rinpoche’s longtime students from California declared out loud at a festive gathering that I was extremely lucky as a beginner to be going on the three-month retreat. As if adding a special dressing to our salad lunch, he leaned toward me confidentially and intoned, “Your karma’s really speeding up.”

I had yet to learn what “karma” meant. But I was in a fast lane for sure and more than content.