Toto, We’re Not in Kansas Anymore

“Everybody’s dreaming.”

— Alak Zenkar Rinpoche

My rock bottom came years earlier in 1985, in a Long Island, New York hospital. I pressed the buzzer that connected me to the nursing station and asked, “Why are there little green munchkins dancing on my bed?”

“It’s the morphine. They must have given you too large a dose. I’ll tell them to lower the dose or discontinue it,” said the attending physician. Tomorrow the surgeon would be removing the breathing tube from my side; I had undergone a thoracotomy to obtain lung tissue for a biopsy—major surgical invasion of the chest wall.

After surgery, the medical residents examined the fifteen-inch curved incision along the crease of my shoulder blade and unanimously agreed that it was “beautiful.” The surgical elegance of the scar was lost on me. What bikini top could hide such an unsightly red gash? I was thirty-two years old with no spiritual practice, too much self-consciousness, and not pleased to hear that I now had stapled sutures in one of my lungs.

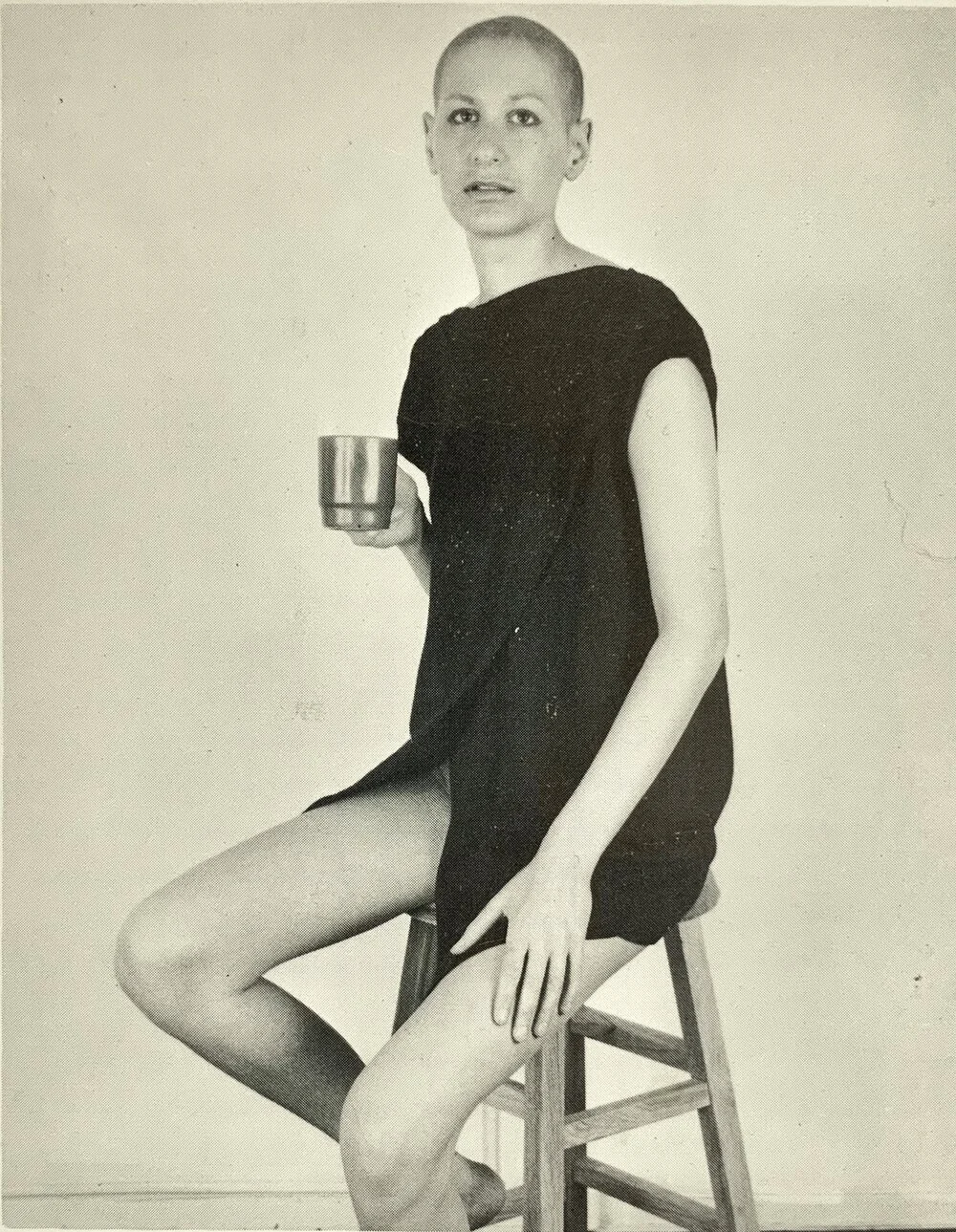

N. L. Drolma, one year prior to wrestling with life-threatening illness.

Debilitated as I was from a cough that had plagued me for months, I feared the worst and prayed to my deceased father for guidance. I sensed I was dying, and it filled me with dread.

The night I received the definitive biopsy report, I panicked. The diagnosis was advanced, non-Hodgkins B-cell lymphoma in my chest and lung. My normal field of vision flattened out like a postcard, and the walls of the hospital room, the bed, the floor, windows and ceiling—everything faded away: there was only thick white space. In that space appeared an apparition of a king in rainbow colors and radiant light. He was standing with scepter in hand, his gaze fixed straight ahead, and wearing a faint smile. I cried out to my father. “Dad, it’s not time for me to go. I must live! ” I prayed with all my might that my normal vision would return.

Moments later, it did. The terror I felt earlier that night also subsided. The statistics for recovery were stacked against me, but I had zero interest in meeting Death. Back in 1985, I knew nothing about Buddhism or its teachings on how to use suffering to access an inner reservoir of equanimity as a basis for clear seeing and intelligent action. I was looking at myself and the world through a huge lens of hope and fear. My circumstances were ideal for the daily practice of meditation, but my radar for meeting a teacher was weak. The social worker at the hospital urged me to read a book by Carl Sagan, which led me to mentally zap my malignant cells with healing light. I resolved to do whatever it might take to get well. After my discharge from Long Island Jewish Hospital, I moved back to Manhattan and entered New York Hospital for treatment under the care of a leading specialist in hematology and oncology.

Dr. Coleman gave it to me straight. There was nothing to lose. He was going to bomb the hell out of me with chemotherapy. A week before chemo treatments were to begin— with a guaranteed side effect of one hundred percent hair loss—I agreed to get my long hair bobbed to avoid a mess.

The hospital’s unfriendly beautician was heavy-handed and careless in braiding a memento. She cut swiftly as if she had a pressing appointment elsewhere and left much of my hair at the foot of the bed. It felt like a hit and run. My “new look” was military, far from the Parisian, gamine cut requested.

“May all matters of vanity go the way of my hair,” I said to myself out loud as I penned the words in my daily journal. Keeping a journal helped me maintain sanity during a taxing course of exploratory surgeries, chemo, myriad tests, x-rays, CAT scans, injections and blood transfusions. The medical acronym for my harsh diet of chemicals—CODBLAM—conjured up for me a cartoon image of a muscular guy clad in a tiger-skin loin cloth, wielding a jagged lightning bolt and the expletive: G-D—DAMN! The image made me smile. I would not be daunted. For eight months, I dined on poison in overkill doses to wipe out the malignant cells lodging in my chest and lung.

Photo of N. L. Drolma by S. Skoglund (1985)

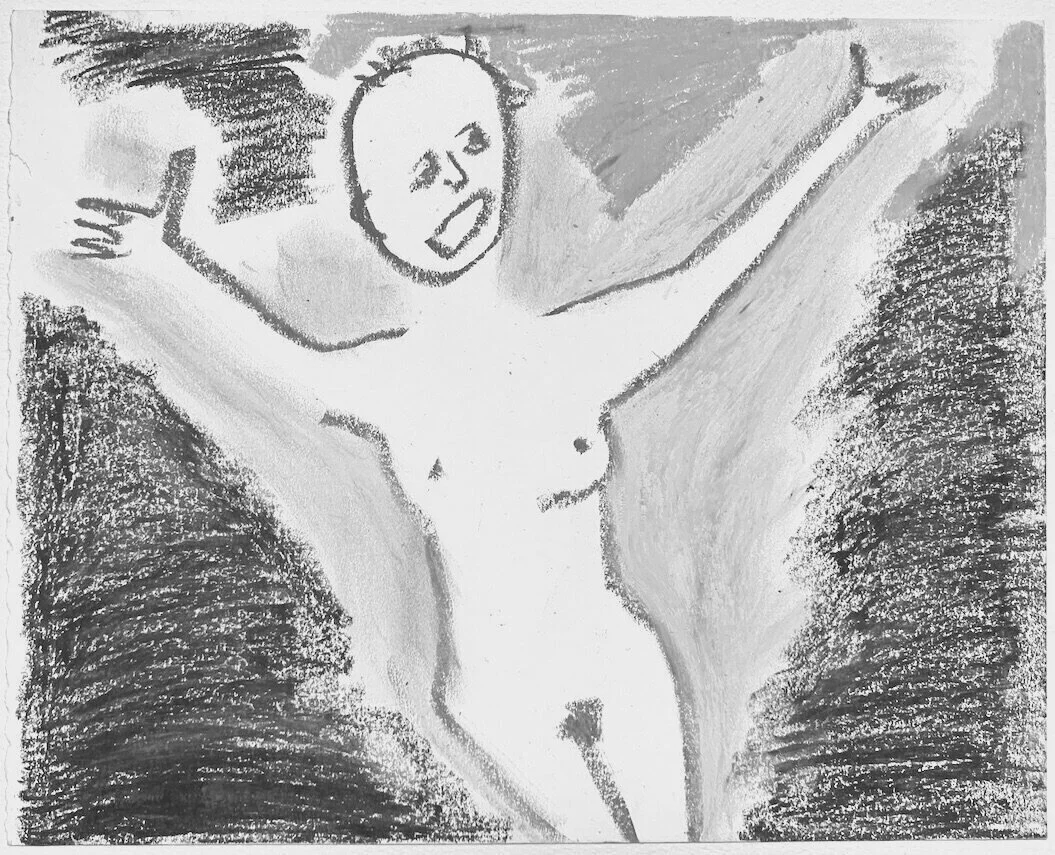

Sketches shown in b/w

Oil pastel by N. L. Drolma from series of self-portraits while undergoing chemotherapy, 1985

“So what if I have to throw up for a year!” I declared with bravado to an old friend who came to visit. (The doctor braced me to spend that length of time in and out of hospital). But after a few months of chemo and twenty minutes prior to another round of treatments, I was asking the attending nurse, “Why are my teeth chattering? Look at me! I’m trembling and the treatment hasn’t even begun.”

“Because you know just how awful it is,” she replied. Her motherly commiseration hit home. My jaw relaxed. All I needed, I guess, was someone to bear witness to the isolating, wretched truth. Nurses are the salt of the earth.

Straightening out my bed sheets one morning, Betsey, my favorite nurse asked, “How would you like to take a real bath?” Although I had been hospitalized for two months, I didn’t know that a swim in a tub was possible.

“Sounds great, when?” What a medicinal treat and welcome alternative this would be to the steamed hand towels provided by the nightshift nurse.

“Now,” Betsy replied sweetly. She encouraged me to rest my weight on her arm as she steered me slowly to the bathroom down the hall. (My muscles were atrophied and my energy sapped.) When I looked into the mirror over the bathroom sink, I was shocked by the gaunt face staring back at me. Betsy insisted on my letting her lift all 97 pounds of me into the tub. I quickly understood why I needed to let her take charge; I could not balance myself without help. She turned on the tub faucets full blast. It was a wonderful, cleansing sound. I also saw for the first time how much of my flesh had wasted away. At five feet eight inches, I was under underweight. This luxurious bath was a visceral teaching on impermanence—my own in particular. But it also was a joyous occasion because Betsey was so caring and gentle. The warm soapy water that she poured down my back and over my breasts felt grand. It was as if all my fears were being washed away in a cascade of primordial nectar.

“I can cure you. If you just keep your head, we’ll muddle through this together.” Dr. Coleman’s words went straight to my heart and to every cell in my body. That same week, a girlfriend surprised me with the gift of a sexy nightgown and told me to ditch the hospital pajamas. She sensed how vital it was for me to keep in mind that I was still very much among the living. I wanted my health care team to see me in that light too, so I preened like a peacock—and let one of the nightgown’s spaghetti straps slip off my shoulder when the doctor came by on his rounds. Flirting was harmless, and fun.

The lustrous beauty of a peacock’s feathers, according to Tibetan lore, is attributed to the bird’s ability to digest a particularly poisonous herb. The more the doctor upped the chemo dose, the more determined I became to show off my resilience.

Postcard image of peacock at Sterling Forest Gardens, NY, a souvenir of my visit there when I was nine years old. Fascinated by the bird’s ornate plumage, I pocketed an iridescent feather that I treasured throughout my teen years.

“The very nature of the peacock is such that it can actually consume poison and thrives on it; hence it does not have to transform the poison but eats it directly. The peacock represents Dzogchen...”(Sogyal Rinpoche, Dzogchen and Padmasambhava, p. 71) Facing death on a daily basis primed me for Dzogchen, the “Great Perfection” teachings of stunning simplicity that liberate fixation on a self that does not exist inherently. But six years would pass before I first heard of Dzogchen, and which resolved my longing for the unnameable.

Early on in the course of my illness, I found comfort in reflecting on the singular intimacy of my father’s last days. One of Dad’s odd remarks at that time pointed me toward an ineffable awareness, a boundless “knowing” that transcends logic and all limitations:

The rules of Long Island Jewish Hospital did not allow me to remain by my father’s bedside for long: he was in the intensive care unit after complications from surgery some weeks earlier following upon a massive heart attack, and his vital signs were fading. I cut and pocketed a lock of his beautiful silvery white hair. I told my dad it was okay for him to go and not to worry about me. He could not speak, but I was certain he could hear my heart’s wishes if not my voice. I was escorted to a small empty waiting room where I stretched out on a lounge and breathed deeply. The tension of the past several weeks fell away and my mind and body relaxed. I felt a profound peace—no separation between us—and sensed, envisioned Dad “departing” through the crown of his head. I was relieved, knowing that he was now free of suffering. I looked out the window: A patch of clear sky silhouetted a branch of sunlit maple leaves. Minutes later, the doctor came to offer his condolences. I checked the hour and thanked the doctor for his efforts.

“That’s about the time the shofar—the ram’s horn—was blown in the shul, said my cousin Lenny who had just arrived from New Jersey. It was Sunday and Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year for devout Jews, the Day of Atonement. I broke out in goosebumps at Lenny’s remark; weeks earlier, when my father had been wheeled back to his room after surgery, he told me that at his death there would be bugles sounding around the world.

~~~

I was pronounced cured, free of any trace of disease—in less than four months of treatment. Naturally, I wanted to quit the experimental protocol. Dr. Coleman, however, said this was not an option. I would have to undergo four more months of chemotherapy; there was too much risk of a relapse otherwise. At this time, I also lost health insurance coverage for being two months past due on a payment prior to the cancer diagnosis. But ocean waves of medical debt were stilled for a while by modest income from my father’s estate and college loans which allowed me to resume classes for a Master’s degree in fine arts.

Oil painting on canvas, 5'x 7' by N. L. Drolma, 1986

The curriculum at Hunter College included a course led by the provocative multi-media performance artist Joan Jonas. We were encouraged to present a theatrical work that had a twist, or edge to it. Inquiry from colleagues about my tango with death was minimal and conversation was generally avoided. Here was an opportune moment to go beyond the strained politesse.

For my term project, I asked the class to form a circle around me with their chairs. I scooted a chair across the linoleum floor to mark the center of the circle, and thus took my seat “onstage.” Sitting motionless, I fixed my gaze straight ahead, focused on nothing in particular. After everyone settled into attentiveness, I proceeded to remove my shoes and socks and placed them neatly at the foot of my chair. Then, rising in a languid stretch of arms and limbs, parodying a stripper, I slipped off the silk scarf from around my neck and slithered over towards a classmate who caught it in his lap. Gypsy Rose Lee I was not, but I walked on full circle—without the prompting of drum roll or catcalls—and unzipped my calf-length skirt, letting its pleated folds drop around my ankles. This prelude to nakedness had no siren’s song or seductive rhythm; I matter-of- factly added my prim cardigan sweater to the mound of scotch-plaid before resuming my seat and with exaggerated slowness, unbuttoned my blouse.

Tell us what came next.

I squiggled out of my sateen half-slip, bunched it up in my hands and pitched it across the floor. Unfastening my pearl necklace and earrings, I spilled them into one of my shoes, my garnet ring and silver Hopi bracelet into the other. With a flutter of eyelashes, I bared a shoulder and shook off the sleeves to my soft cotton blouse. Tossing it high in the air, I watched the white cotton top billow and spread like a blossoming lotus.

Then I motioned for someone to kill the lights. I was down to my bra and bikini undies. The room went dark except for the light spotting my chair, and I moved to unhook my bra—then paused. As if remembering something of great import, I pointed to my elastic headband and plucked at it much as one might test the string on a guitar. My classmates laughed—here was another article of clothing to stall their view of me in the raw. For a minute or more I sat erect and still as a mannequin. Then—as if coming clean for the first time in a millennium—I reached for the headband, and with it whipped off my wig of dark blonde curls. My baldness in lights was the show-stopping moment, which also signaled the end of the show.

N. L. Drolma sporting headscarf and fringe of synthetic curls, NYC,1986 (Student photo ID)

In this, my first foray into performance art, I sought to communicate something both intimate and universal, beyond the written or spoken word or painted image. The performance shocked my classmates and it highly irritated a few who felt the skit was more fitting for a therapist’s office. Days earlier, an acquaintance spotted me at a Soho gallery on West Broadway and sang out, “Great-looking perm! Curls really suit you!” I acknowledged the compliment with a nod and wan smile. Her remark pushed me to reflect on the cosmetic deception. Was it still necessary? In the early days of my illness, the fabricated curls cheered me up, and I enjoyed “fooling” people; I made a decision back then to keep mum about my health (unless prodded), because on occasions when I had volunteered the fact that I was ill with cancer, my candor elicited awkward silence, or platitudes that cut short honest communication, creating distance. Now, however, I was no longer in acute crisis, and my silence, another sort of “wig,” was due to be shed.

One evening following on my performance at school, I slipped into a slinky dress and low patent leather heels, adorned my eyes with shadow and liner, my lips with gloss, my long neck with pearls, and my ears with Mexican silver. Clutching a vintage beaded purse, and leaving my wig in its drawer, I stepped outside into the city’s bright lights and traffic. It was my first time out in public not wearing Shirley Temple’s mop of curls, and the night air against my skull felt heavenly. I headed for the Palladium in Union Square, which was the vibrant new club for the downtown art crowd. This population knew how to flirt and party in the dark. Strobe lights, tinsel, and pulsating music flooded the edgy atmosphere. This was live theater with no division between audience and actor. The dance floor was a welcome contrast to the 17th floor at New York Hospital, where I had lived on and off over a span of nine months. At the disco, unlike at school, I could show up “naked” and not offend anyone.

On the day of my discharge from New York Hospital after my last chemo treatment, I felt a tremendous sense of accomplishment as I walked through the exit doors of the hospital, out into the sunshine and hailed a taxi from East 69th Street & York to my apartment on West 14th. The world looked so intensely bright and colorful. What to do now with my glorious freedom? I was like Dorothy in the Land of Oz, looking at everything with a child’s wonderment. I wandered into a local food mart. “Oh—strawberries!” I said to myself out loud. An onlooker asked derisively, “You haven’t seen strawberries before?” I just smiled and made my purchase. I felt as if I had been to the moon and back. In the days and months that followed upon my medical triumph, I so wanted to make sense of the experience, integrate it purposefully in my life—and share it with others. By dint of circumstances, I found myself mulling over a line by W. B. Yeats:

“To be secret and exult is of all things known the most difficult.”

Photo of N. L. Drolma by S. Skoglund, NYC 1985. Image served as postcard for art show the following year.

What had I yet to learn that could allow me to rest at ease with my heightened awareness of death?