Appleness

Spontaneous appearance of the Lotus Dakini and Mani mantra in Stanley, Virginia, 2014 (Photo/illustration by N. L. Drolma)

Frank discussion about celibacy is taboo but needn’t be. The following quote of Chogyam Trungpa (Work, Sex, Money p. 118) might quell a few assumptions and inspire useful dialogue:

“Within the Buddhist monastic tradition, there is a traditional, orthodox, and very disciplined way to work with passion in order to go beyond possessiveness and grasping... until you reach the point of passionlessness, where you realize that putting passion into action and not putting passion into action are the same… [C]elibacy is a powerful way of dealing with desire, not by suppressing passion, but by examining the mental aspect of it.”

Of the major vows taken by a Buddhist renunciant, the celibacy vow is the vow that most impresses, frightens, or befuddles laypeople. (It has also elicited glib, misleading remarks on social media by a few Vajrayana practitioners who apparently don’t know better.) Padmasambhava, the Indian mahasiddha who brought Vajrayana Buddhism to Tibet, points out matter-of-factly that sexual union is the downfall of most yogins. Likewise in the writings of Tibet’s revered dzogchenpa, the “Omnisicent” Longchen Rabjam, practitioners are advised not to rely on the body of another if they wish to actualize their enlightened nature. The caution advocated by these two renowned masters, plus honest introspection, helped me look at sexual passion and all other desires from an uncommon perspective.

Polaroid of 30 year-old N. L. Drolma

~~~

Prior to falling in love with the dharma, I loved dancing, I loved flirting, and most of all, I loved creating something out of nothing with oil paint on canvas. I also entered into passionate liaisons somewhat mindlessly and even (sort of) “fell in love” a few times.

My first head-over-heels tumble was with Avery, the most popular English professor on campus. He was a poet in his late twenties, married, and the father of two toddlers.

“What do all apples have in common?” the professor asked. Some of us freshmen exchanged quizzical looks. What sort of English lit course had we signed up for? It was fall semester and the first day of class. After the professor vetoed a few lame guesses by my classmates, I raised my hand. “The core,” I said matter-of-factly. This won a smile from the tall, thin, long-limbed preceptor who conceded that my answer wasn’t bad, but not The Answer. He then strode over to the blackboard and drew a large circle, symbolic of an apple whose radius equaled his arm span. He continued to energetically draw circles on top of circles as if elongating a slinky toy.

“Appleness,” he said, turning to us. “Appleness.”

Appleness? I was intrigued.

Five stars to you dharma brats who would have crowed, “Suchness!”

Right from the professor’s opening salvo and from the seductive, angular dance of his body as he expounded on appleness, I knew for sure I was going to ace the course. My interest in the course work simultaneously billowed into an intense crush on the teacher, which inspired studiousness on my part and distracted me from the romantic overtures of available boys who were my own age.

N. L. Drolma, age 16 (high school yearbook photo)

In high school, I had been shy and awkward around boys; I liked the tall brainy boys who had eyes for the short girls. I also liked the boys who preferred no girl to their science projects. (Are any Millennials or Gen Zs reading this similarly afflicted, or has social media stoked numbness and preternatural adulthood?) At age thirteen, I was tall, thin, all arms and legs and big feet. I bemoaned my flat chest and the pageboy cut of my straight hair that allowed no hint of mischief. I thought I was funny-looking with a nose and ears too big for my face; pretty were petite girls who wore bouncy ponytails, frilly dresses, and knew how to talk, laugh, and run around with boys. On turning seventeen and entering college, however, I dressed in hotpants, platform heels, and let my hair grow long in braids. I was tired of being shy; my self-deprecation as a young teen was a lingering shadow that needed sunshine. Had I practiced meditation throughout my childhood years and been privy to the most basic dharma teachings on compassion, would I have suffered low self-esteem as an adolescent? —Unlikely.

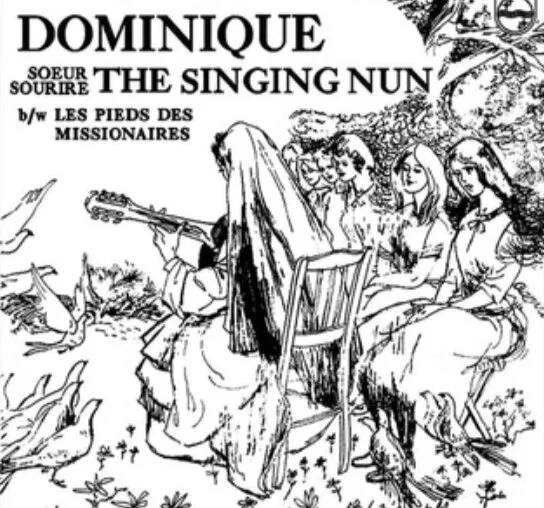

That same year marked Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s arrival in America. Students in New England and elsewhere were gathering to hear Rinpoche’s dharma talks on work, sex, and money, teachings that would have helped me release a few inhibitions for sure. However, I had yet to even hear the word “dharma.” Instead, my ears were attuned to the Beatles’ Abbey Road album whose lyric Here Comes the Sun seemingly resounded through the corridor of our girls’ dorm at all hours. Occasionally, I’d closed the door to my room, cue up my record of The Singing Nun, and sing along in French. The spiritual content of the lyrics made no overt dent in my consciousness. I just loved the tunes.

Cover photo of the Beatles album featuring their mega hit song, “Here Comes the Sun.”

The Singing Nun…a far cry from the Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, Bob Dylan, and the Mamas and the Papas.

In my freshman year at college, I spent most “nights out” among the campus library’s stacks and in the elegant Edwardian reading room when I was not on my part-time job at the circulation desk. The job was ideal for meeting what felt like the entire school population, and I practiced flirting while stamping the due dates in the books of hip looking guys that normally would not look twice at a girl who wore glasses and no lipstick. Unlike the coeds who were determined to meet their Prince Charming, I set for myself the less ambitious task of becoming more open and social with everyone (but eschewed the ear-splitting acid rock frat parties).

In the first of several literature classes I would take under Avery’s tutelage, I read Saul Bellow’s short story A Sermon by Dr. Pep, which turned me into a vegetarian overnight. It hadn’t occurred to me that all the hamburgers, seared lamb chops, and chicken breasts I enjoyed in this lifetime were body parts of sentient beings who never wished to be slaughtered, gutted, packed in ice and sold as food for my consumption, or anyone else’s. When I came home for the school holidays and saw the soup pot with chicken feet sticking out of it like an elderly lady’s withered hands of knuckle and bone, I let out a geshri (that’s Yiddish for a piercing wail) and informed my parents that no one should partake of such a culinary “delicacy.”

Twelve years later, Avery and I ran into each other on a street corner in the Chelsea district of New York; it was a mutually joyous, utterly dreamlike encounter. Divorced, he was living alone in a brownstone garden apartment, only two blocks from my cookie-cutter high rise on 14th street and 6th ave. Avery had quit academia and was working as a copy editor. He was also quick to let me know that he was in his third year of sobriety, thanks to Alcoholics Anonymous. My eyes sought heaven in disbelief when Avery revealed that he kept a bundle of poems and letters I wrote during my college career. Now, he would turn to me as his Muse and write poems that were measured and rhymed. The romantic relationship I dreamed of as a naive undergraduate, and which took well over a decade to blossom, reached a karmic impasse in less than eight months. Ah, well... actually, the ending wasn’t ah well. It was a…awwwful.

Years later on hearing the Buddhadharma, I was moved to look inward, deeply. I sensed that my inquisitive nature and energy expended in intimate relationships could be harnessed for the better by embracing the dharma 24/7. Devoting more time and energy to dharma practice and less to any love story is profoundly gratifying, and less complicated.