Could Maroon Be the New Black?

View from taxi en route to Rigdzin Drubpe Ghatsal Monastery, Yangleshö, Nepal (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

~~~~~~~~~~

For a vivid glimpse of life as pure illusion, a taxi ride up the mountains from Boudha to HH Chatral Rinpoche’s monastery in Pharping can suffice.

HH Chatral Sangye Dorje Rinpoche (photographer unknown)

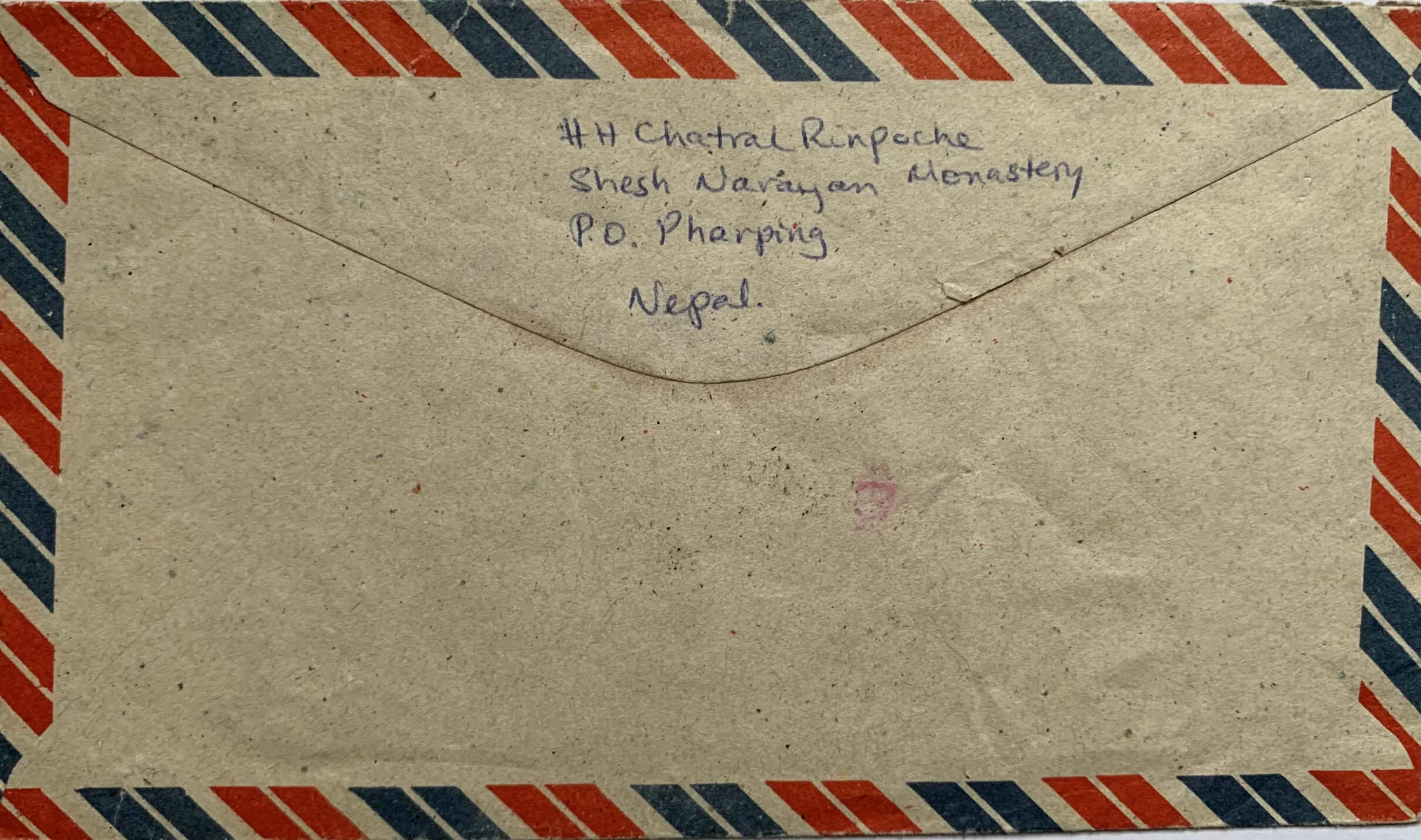

It was September 1996, more than two years since my first meeting with Chatral Rinpoche, and I was back in the monastery’s waiting room having triumphantly extricated myself from life in New York. (You could say this was a big time dream come true, but from a Buddhist perspective I was still dreaming.) I carried with me a letter I received from Chatral Rinpoche the very afternoon I vacated my apartment in New York City. Only minutes before the town car arrived to speed me to the airport, I had a sudden urge to check my mailbox and found the mind-stopping envelope with its Pharping postmark, stamped images of hyena and lynx, and on the top fold—HH Chatral Rinpoche’s address.

For my trip to Nepal, I could not have received a more auspicious sign. Emaho! How amazing is dharma! I was flushed with wonder as I read the full-page letter. I could hear Chatral Rinpoche’s no-nonsense voice, and I winced and chuckled at his wrathful orneriness, especially when I read the following admonishment: “Please ask Zenkar Rinpoche your Dharma questions. I have heard he is quite learned in Dharma, so please ask him, not me.”

It was Alak Zenkar Rinpoche who counseled me to study with Chatral Rinpoche in Nepal. Great masters may choose to examine a student for a long time and test the practitioner’s motivation and commitment before giving one word of teaching. Chatral Rinpoche didn’t give teachings readily. However, I was certain that if I followed Zenkar Rinpoche’s advice, unique conditions for teachings, study, and practice would blossom.

At my meeting with HH Chatral Rinpoche in his room overlooking the towering trees and sacred waters of Pharping, I spoke briefly about my masters and flashed the photos of them that were tucked in my wallet. Chatral Rinpoche inquired specifically about Nyoshul Khenpo’s health. I then confessed to Rinpoche that I wasn’t smart enough to know what question to ask of him. However, if he had any heart advice for me prior to my taking nun’s vows, I wished to hear it.

Chatral Rinpoche did not mince words. “Robes and haircut don’t make a nun.”

This, I was happy to hear. Cultural trappings do have their efficacy and inspire countless people, but I myself was not keen at the prospect of wearing robes. Just as clothes don’t make the man, monastic garments do not magically tame one’s mind. Yet it was also easy enough for me to appreciate the wearing of robes as a reminder to oneself and others of the Buddha’s renunciation, and of one’s commitment to actualizing the wisdom of egolessness.

As I was about to take my leave from the precious master, I was heartened beyond measure when Chatral Rinpoche said he wanted to see me back in Pharping after my ordination, and robed in red.

Lama Khyenno. Lama, you alone know.

~~~

Flights to Nepal’s remote mountain region of Solukhumbu were infrequent and I had a narrow window of calendar time to request ordination: H. E. the 11th Trulshik Rinpoche was more often than not in solitary retreat at his monastery Thubten Choling.

Thubten Choling Monastery, Solukhumbu, Nepal, Winter 1996 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Detail of mantras carved on rocks along the trekking route, Solukhumbu, Nepal (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Trulshik Rinpoche Ngawang Chokyi Lodrö conducting tantric ritual at Mani Rimdu festival; featured in the film, Lord of the Dance, Destroyer of Illusion (Photography Jean-Francois Aloisi)

To skirt an impending labor strike and ban on motor vehicles or otherwise miss my flight to Solukhumbu, the Dragon Guest House arranged for a car to take me to the airport at 4:30 a.m. Strikes often immobilized a huge chunk of the Nepali landscape and, like a monsoon, signaled a washout of the day. I was three hours early for a thirty-five-minute flight to the hill town of Phaplu. My morning flight to Phaplu was on hold—it’s time for departure anyone’s guess—and all afternoon flights at Tribuvan were cancelled.

My useless thoughts scurried across the deserted lobby and crashed into the stacked metal rows of empty baggage carts. I sat on my bags and prayed for a clerk to appear behind the Royal Nepal Airlines check-in desk. Nepal is the ideal country for teaching Westerners patience.

Five hours later, I was strapped into the windowed seat of a quaint prop-jet for a scenic flight and “Lost Horizon” view of Mt. Everest and its neighboring chain of ice-capped mountain peaks. It looked like a drawing in the sky made with a fine icing gun for decorating wedding cakes. Why, I wondered, would anyone want to scale those frozen edifices? But intrepid mountain climbers might equally wonder why any spirited, sane American woman would trek to the foothills of Mt. Everest to be ordained as a Buddhist nun.

Two monks, two nuns at Thubten Choling monastery, Solukhumbu, Nepal, Nov. 1996 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

The plane landed on a precipitously narrow mountain plateau within a hop and a skip of the local inn. Upon entering, I was ushered to a bench and low table around which several trekkers were enjoying generous dishes of steaming hot rice and dal. Tea followed with three Tibetan women who were to be my trekking companions. It was nearly noon and we had six or eight hours of trekking ahead, so I was eager to set off.

This was my first trek ever, and for a city slicker who hadn’t bothered to consult a travel guide, the trek was exhilarating and leavened with humor. Only one of my Tibetan companions knew any English, and I spoke no Tibetan, so there was no conversation to distract me from the unparalleled beauty of the mountain vistas. In a spirit of camaraderie, however, I learned the Tibetan word for beautiful: Arms akimbo, I whirled about and proclaimed effusively to the mountains and the sky, “Zebo! Zebo! Zebo! This is soooo much nicer than New York.” I thought to myself, ‘Someone pinch me. This is no ordinary landscape. I’m in an exquisite buddhafield.’

Trekking companion alongside gigantic boulders incised with mantric syllables. Thubten Choling nestled in the distant hills. (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

The other word I learned out of necessity was sangcho, because a toilet is what I needed badly, and the open terrain was too open for me to relieve myself discreetly. I squatted theatrically and waved tissue paper to the bafflement of my companions. (Toilet paper is not part of their culture.) Eventually they understood my charade and my plight. I was a big city girl from America and first-time trekker who had no backpacking skills whatsoever.

My physical frailness—in stark contrast to the mountain goat nimbleness of my Tibetan guides —was proof that cultural habits literally can make a person weak and wobbly. Unaware of a walking stick’s usefulness, I was without one but not to be deterred. I was happy and drunk on the vast blueness of the sky, the fresh air and apocalyptic waterfalls, and friendly ruggedness of the landscape whose awesome truth I could not possibly capture with my Canon 50mm lens. This adventure was just beginning and absolutely everything was zebo! It was bliss to be part of the landscape, and easier to keep the camera in my backpack. I promised myself to shoot a few rolls at the monastery and on the return trek to Phaplu.

“As the main approach to Mt. Everest, the Solukhumbu region has an almost mystical status in the world of trekking.”- Lonely Planet Guide. (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

It was now late afternoon and my trekking companions and I were sitting around a fire pit in the rugged home of a local Sherpa, snacking on piping hot small potatoes—peeled for me by our host whose fingernails were embedded with grime, thick and black as any of my Ebony charcoal drawing pencils. He was generous with the little he had, and his smile was guileless. At the waning light of dusk, I learned of “our” plan to spend the night in Junebesi, a small Sherpa village. This mountain region had a magical air. Along the stone-fenced winding path, huge boulders—incised with intricate mantras—only needed to be lit up by the Cheshire Cat’s ethereal smile to confirm that all was just a dream, pure make-believe. Early the next morning, we would depart for Thubten Choling Monastery.

I was overjoyed to be only hours away from having a private audience with Trulshik Rinpoche. In one of his many illustrious past lives, Trulshik Rinpoche had been Ananda, the Buddha’s close disciple who openly advocated ordination for women as well as men. Was I really going to do “the nun thing”? (That question was whispered to me by more than one friend back in America.) It was supreme good fortune to be ordained in Trulshik Rinpoche’s unbroken lineage of accomplished practitioners.

The clouds were hanging below where I stood a bit giddy, at an elevation of 9,000 feet; I felt even higher, and light-hearted for having finally arrived at Thubten Choling. The environment was beatific, exceeding hallelujahs.

“What are you doing here?” Ani Jinba inquired dryly, as if I had just walked around the corner to order a roast beef sandwich at the local deli where it’s well known I don’t eat meat. The gifted translator looked quite comfy seated on her bed in a commodious, light-filled room that was situated only yards above the monastery’s outer courtyard. She was among the first Europeans to be ordained in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, back in the late 60’s and early 1970’s. We had last met in 1994 in her flat in Amsterdam.

“I’ve come to request ordination from Trulshik Rinpoche,” I said to Ani-la. I was bubbling over with happiness.

“Well, Rinpoche’s very busy,” Ani Jinba declared, so busy that she didn’t see how he could possibly grant vows. I let Ani-la’s comments dissolve into the thin air. This day was a magnificent turning point in my life. She herself was very busy, engrossed in translation when I showed up at the door and I clearly interrupted her at an inopportune moment. The tepid welcome had a humor of its own given how far away we both were from our respective homelands in the West. It was also humbling to recall my first meeting Ani Jinba at Lerab Ling in 1993 and my ignorance at that time about what it meant for a western woman to take on a nun’s commitment to the buddhadharma.

At my meeting with Trulshik Rinpoche the next morning, Rinpoche’s face broke into a bright, wide smile when he heard that I had come with robes at the ready. (On the advice and with the kind assistance of Ani Chödrön, a devotee of Dungse Thinley Norbu, I purchased the requisite maroon cloth in Kathmandu and engaged a tailor in Boudha to fit me in robes.) I hadn’t prepared for the haircut, however.

Mala and my shorn ponytail, Thubten Choling Monastery, 1994 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Ordained name “Ngawang Lodrö Drolma” written by Trulshik Rinpoche on official letterhead

Two weeks later, I was bald as a light bulb and without the traditional red-colored cap to shield me from the cold night air and the day’s burning sun. It was an oversight during the hurried tailor preparations in Boudha, which I remedied by offering rupees and earnest pleas for the frayed brown headscarf worn by the sweet nun who brought breakfast to my room throughout my stay at Thubten Choling.

After the morning’s ceremonial haircutting in the outer courtyard and the vows of ordination in Trulshik Rinpoche’s chambers, everything felt more than a bit dreamlike. A softness and quiet suffused my entire being, and after lunch with one of Rinpoche’s close attendants, I spent the afternoon in solitude. Auspiciously, it was Guru Rinpoche Day. In the evening, as I took my seat in the shrine room in the presence of a group of dharma students from Switzerland, my quietude gave way to acute self-consciousness. Shocked gazes and a few loud whispers among them made me feel more naked than any nude model for an American university art class.

Ego was already having its way with the fledgling renunciant.

~~~

Three sweet nuns of Thubten Choling, Solu Khumbu, Nepal 1996 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Tibetan elders spoke of Thubten Choling monastery and its rugged environment as akin to “Old” Tibet, predating China’s invasion. Blessings were in every inch of the monastery’s flagstone and bag of grain, in the twinkling eyes and bright smiles of the monks and nuns, and in the weathered faces of the Sherpas and Tibetan nomads enjoying their tea and tsampa after having met with Trulshik Rinpoche. Blessings were embedded in the patina of the monastery’s weathered paint-chipped walls, wooden benches, decorative ceiling and wall hangings, and in the soot-faced cook (her nose and cheeks smeared for lack of a chimney in the monastery kitchen). Punctuating the wonder and charm of it all were the dzos, hybrids of cow and yak nuzzling in the outer courtyard, and the fairytale view through my casement window onto the inner courtyard and over the rooftop of the lhakhang, the Tibetan temple, where numerous black crows would gather during the morning wakeup call of the conch blower.

My blue jean days were over.