Short Hair and Love in Sikkim

~~~~~~~~

“The yogin who, having given up worldly activities, is without selfishness and personal objectives, is always happy.”

— Milarepa

My makeshift quarters at Chatral Rinpoche’s monastery in Salbari, India 1998; it was razed later in the year. (Photo by N. L. Drolma),

In winter of '98, I made my first visit to Chatral Rinpoche’s gompa in Salbari, India where I was housed in a cavernous, gutted abode of cement that had been the monastery’s former kitchen. It was palm tree weather during the day, but bitterrrrrrr cold at night; after a week’s stay, I came down with a whopping chest cold.

Chatral Rinpoche arrived in Salbari some days later and told me not to hang around for Nyungné—the fasting practice held annually at the gompa. This was fine with me because I needed food, and food I could digest, not the local popular “emadatshi” stew of hot chili peppers and yak cheese that looked to me (and tasted) like regurgitated pizza. I was warmed by Rinpoche’s sonorous voice and big beautiful hands as he proceeded to tie a wide red ribbon around my neck; I was leaving for Sikkim to practice at Chorten Gompa. Rinpoche handed back my offering of the Disney figurine I purchased in Hong Kong—a red-haired mermaid holding a purple conch shell—and instructed me to give it to Dodrupchen Rinpoche.

◊

Fine food and lodging in Sikkim was made possible for this renunciant by an off-season rate at Gangtok’s Hotel Tibet, plus the hotel’s offer of a gracious dharma discount. It was a nice change of pace and a great location too. I enjoyed invigorating walks down the main road through town to Dodrupchen Rinpoche’s monastery, Chorten Gompa.

“May all our meetings for all of our lifetimes be as sweet as this tea, even sweeter,” I cupped my hands and voiced this aspiration on meeting Dodrupchen Rinpoche’s consort, Khandro Pema Dechen of Kongpo. The wisdom dakini laughed, nodding her head enthusiastically as if assenting to my wish. Her room was small and cozy, and its window looked out onto the impressive chorten and the steep tree-lined road leading up to the monastery. It was the perfect setting for a welcoming cup of Solja, the delightful blend of Assam and Darjeeling that was served by her monk attendant every morning, along with a dainty china plate of biscuits.

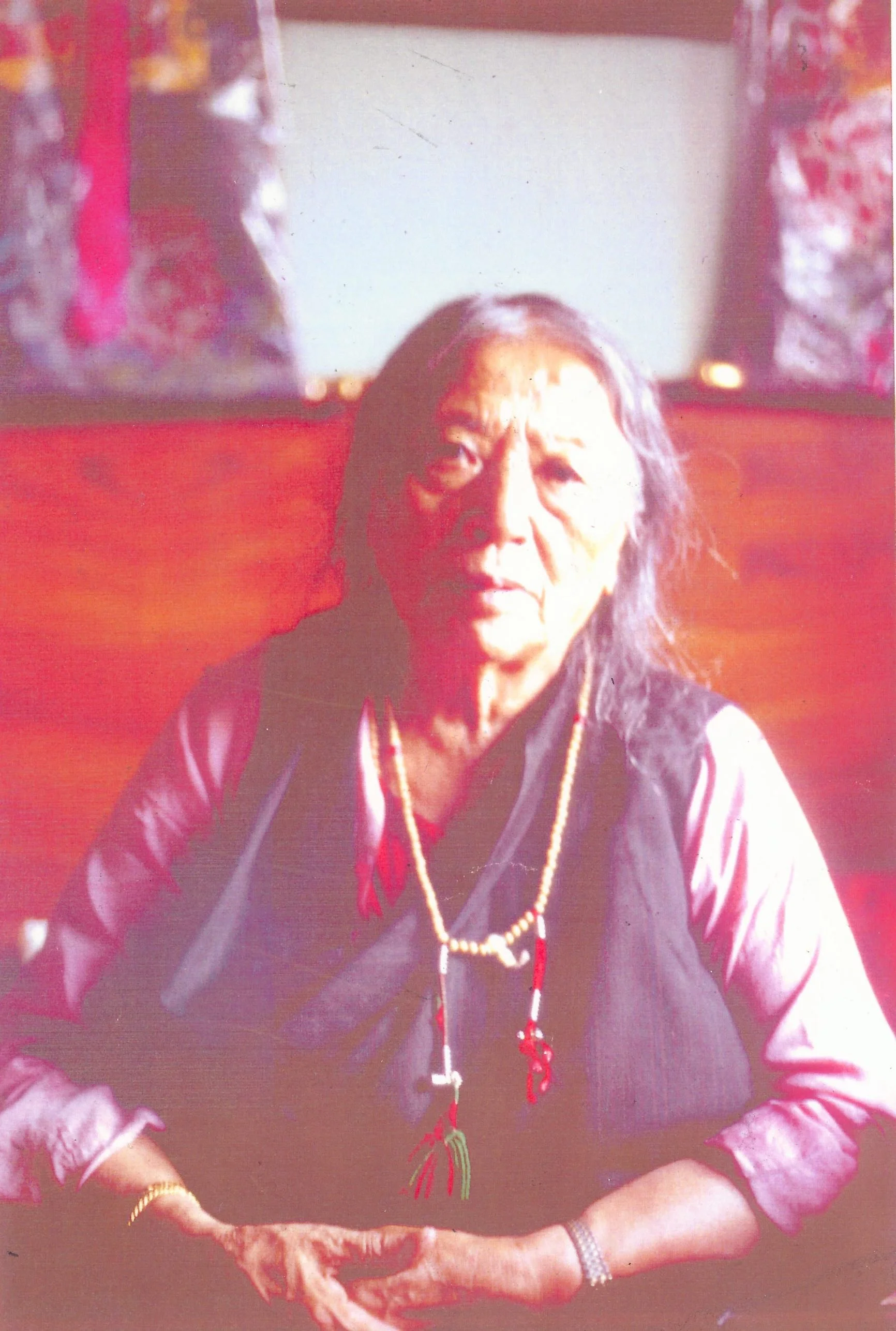

Chorten Khandro Pema Dechen (Photo by M. Carrigan)

Chorten Khandro Pema Dechen’s manner was disarming, without affectation, marked by precision and a cool awareness. Her entire being was one with her guru, Dodrupchen Rinpoche. I much appreciated her several invitations to lunch as well as daily morning tea. Khandro-la laughed good-naturedly and thanked me when I told her how I wished she would visit America and stay at my place in New York. Khandro-la confessed that she’s been invited to go everywhere in the world, but Dodrupchen Rinpoche vetoed all such travel; Rinpoche didn’t even like her going into the streets of Gangtok. There is a Buddhist adage that a yogin should wear out his meditation cushion and not the soles of his shoes, i.e., go nowhere—just sit. Dodrupchen Rinpoche himself rarely traveled.

◊

Chorten Khandro was inspired to orchestrate a “debate” between me and a long-nailed Tibetan tulku (incarnate lama). The tulku was annoyed that I let my hair grow a few inches, in marked contrast to the severe buzz I wore on a previous visit to Chorten Gompa. He felt it was an insult to the buddhadharma that I, a Buddhist nun, eschewed the discipline of a shaved head. Apparently, my short hair was a no-no and warranted investigation. For our sparring sessions which were held in her room, Khandro-la secured a young translator from Darjeeling who was visiting Dodrupchen Rinpoche and happy to take part in such dharma merriment.

During our second and final debate, the tulku’s negativity toward me escalated beyond reason. Khandro-la diffused the tension by entering into the fray with skillful levity and said, “Ani is so compassionate. By letting her hair grow, she is making a home for lice.”

The translator, the tulku, and I burst out laughing and we turned appreciatively toward Khandro Pema Dechen, who then met our hearty laughter with her own. The prickly exchange was nearing resolution.

I asked the tulku if he knew how many Tibetan Buddhist nuns were living in New York City. He ventured a guess: one hundred fifty or maybe two hundred.

Snapshot of Chorten Khandro Pema Dechen and N. L. Drolma, Chorten Gompa, Sikkim, 1998

“In the City that Never Sleeps whose population exceeds eight million inhabitants, there resides only one Tibetan Buddhist nun in the Nyingma tradition, the native New Yorker sparing with you here at Chorten Gompa.” The tulku’s eyes rounded with surprise. He now had a keener sense of the cultural divide I was navigating as a white girl robed in maroon.

As we were parting, I asked the tulku playfully why he let all his fingernails grow long and not just the pinky nail, which is a cultural habit in certain regions of Tibet. “No scissors” was his reply.

The dharma is so vast and deep—way, way beyond accepting or rejecting a tulku’s long nails and a nun’s haircut. It would be so nice if the tulku and his fellow Tibetan lamas could simply rejoice for any dharma practitioner (lay or ordained) born in the West whose life is one with the dharma.

Chorten Khandro’s sparkling eyes—the eyes of a great dakini—reflected the tears of countless beings and the clear untroubled waters of wisdom. “Ani Lama” was her nickname for me. Perhaps she addressed me in that way to inspire my diligence as a chopa (dharma practitioner). Khandro-la knew I had no compelling interest or involvement in mundane affairs and that I loved sitting in her room, and sitting alone in Chorten Gompa’s unadorned temple. The temple was truly minimalist for a Tibetan lhakhang. It resembled an artist’s large, empty loft; the bare light bulbs hanging from the ceiling were the most eye-arresting feature of the space. The ceremonial trappings were few, and I liked it that way.

Although I never sought to be photographed with the great masters I met—I liked being the one behind the camera—I heartily accepted a visitor’s spontaneous offer to snap a picture of me with Chorten Khandro. During a subsequent stay in Sikkim two years later, I requested from Chorten Khandro Pema Dechen a lock of her hair. Khandro-la graciously complied. Om Pemo Yogini Jnana Varahi Hung !

Close-up of chorten at Dodrupchen Rinpoche’s monastery, Gangtok, Sikkim (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Monsoon rains left me stranded and dripping outside Chorten Gompa’s temple late one afternoon, well past four o’clock, the last hour in the day when taxis bother to drive up the steep hill from town to collect a fare. Peering into the only parked car on the grounds by the monastery’s towering chorten, I was delighted to see a talisman with HH Dudjom Rinpoche’s picture dangling above the dashboard. Moments later, the car’s owner appeared—a charming Tibetan tulku who was pleased to rescue me from the nonstop rain. I gladly accepted his offer of a ride and an invitation to his home for tea, which he assured me was but a short detour from my hotel. He was roundish and energetic with an engaging, dimpled smile and intense eyes that reminded me of an old ex-boyfriend. It was also uplifting to meet a Tibetan lama whose understanding of spoken English allowed us to communicate with ease.

Framed and hanging on a wall in the tulku’s house was a large photograph of himself with one of my teachers, a preeminent master in the Nyingma lineage. It was an impressive image. I politely looked through several photos of him with other masters, and the tulku then played an audio tape of himself chanting prayers. He did have a beautiful voice. But I grew restless listening to the tape. I had sat in the monastery’s temple for most of the day, now it was time for bed. I drew my host’s attention to the late hour. He understood, and after we enjoyed a delicious homemade thenthuk (flat noodle soup), he drove me back to Hotel Tibet. My room was on the second floor. The tulku accompanied me up the stairs and invited himself in. I was tired and only vaguely amused.

He made his way over to the large picture windows that faced onto the boulevard and swiftly closed the curtains. This brazen gesture erased my fatigue. “What are you doing?” I asked. My eyebrows rose higher than Mt. Kailash. Smiling, the tulku sat down at the edge of one of the twin beds, a few arm-lengths across from where I was sitting on the other bed, and took my hands in his.

“I think I love you,” he said. It had been a long day.

“You - think - you - love - me,” I replied, repeating his words slowly.

“Yes,” he said.

“What do you mean, you think you love me?! Don’t you know for sure that you love me?” The tulku looked at me blankly.

“You mean you want to be with me tonight. You want to, uh, sleep with me. Yes?”

“Yes,” he said smiling.

“But—I’m an ani, can’t you see that?”

“Oh, that’s all right,” the tulku replied.

“Uh, no it’s not.”

“No problem. Nuns can have boyfriends,” he said emphatically.

“They can? I don’t think so. I don’t recall taking such a vow.”

“Yes, nuns can have boyfriends.” The tulku then told me about Sikkim’s sacred sites that he would take me to in the days ahead.

Interior view of Chorten Gompa’s temple, Gangtok, Sikkim 1998 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Image of Ariel, evocative of the mermaid figurine I offered to Rinpoche.

But I was not one to be lured into a mindless frolic. It was my understanding that dharma practice employing sexual energy was for advanced yogins and that self-deception in this practice was subtle, and the ruin of many practitioners. I addressed the tulku’s desire directly:

“Well, not this year. I like being ani, but Dodrupchen Rinpoche knows best about these matters.

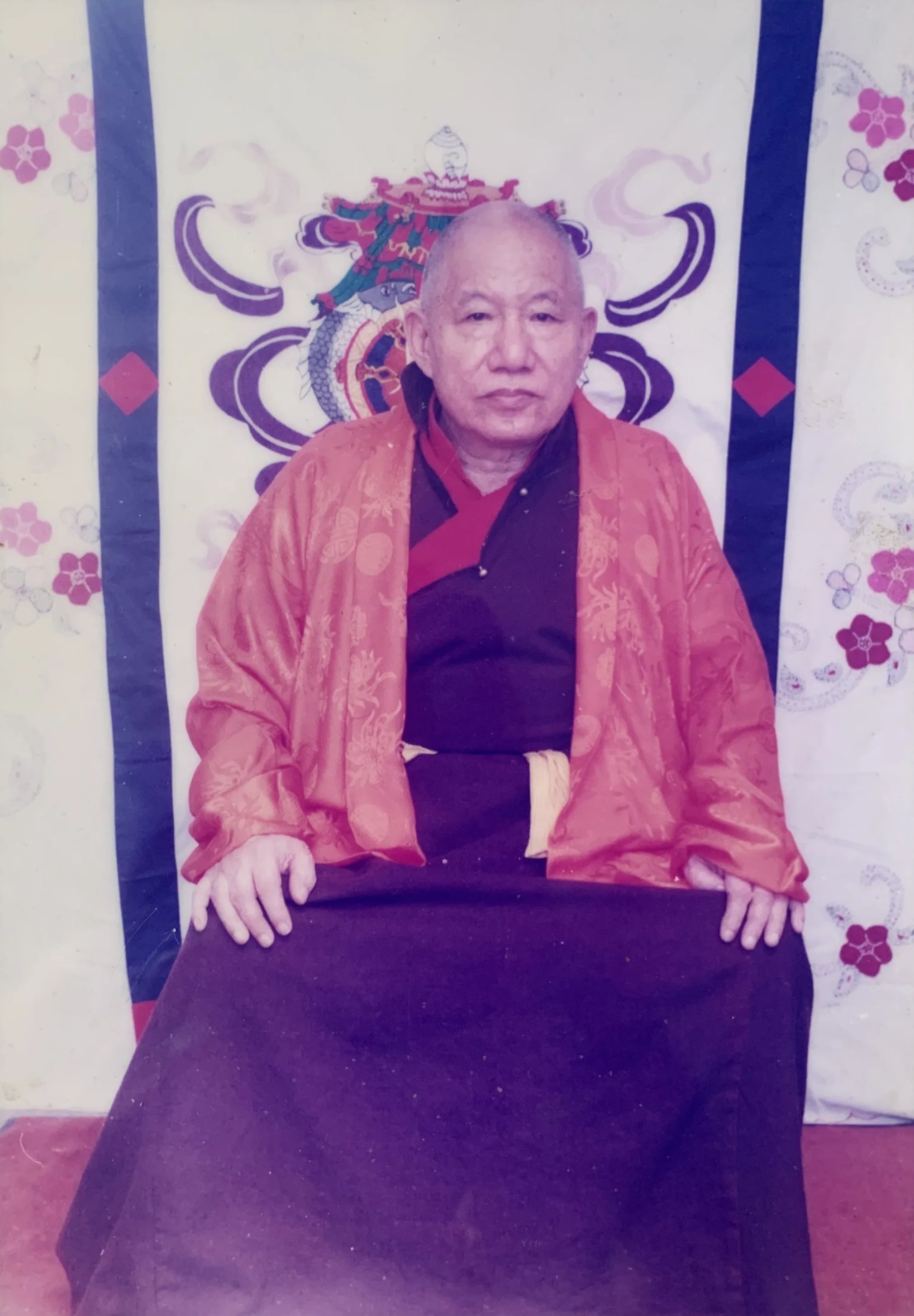

Dodrupchen Rinpoche (Photographer and year unknown)

If Dodrupchen Rinpoche says that it would be good for us to be together for our dharma practice, then, yes, I would be pleased to be with you. We can ask him to do a mo.* ”

The tulku’s face darkened beyond patience. I saw him to the door and wished him “goodnight.”

* Tibetan term for divination

Postscript:

Chorten Khandro Pema Dechen passed away in the fall of 2006. Miraculous signs of her attaining rainbow body were witnessed publicly by hundreds of Asians and westerners.*

* “At the time of her passing, she [Chorten Khandro] remained in meditation for days. During her cremation, the sky was filled with rainbow lights. These were not just beams of rainbow light, which are not that rare, but thigles, circles or sphere of rainbow lights, which are multiple colors, sizes, and designs. They are signs that every particle of the physical form is being transformed into pure light, and it all is being absorbed into the Ultimate Pure Sphere...” Source: Tulku Thondup, Incarnation.