Once in a Lifetime

And you may ask yourself, “How did I get here?”

— David Byrne

Car ride through Thamel, Kathmandu (photo by N. L. Drolma)

~~~~~~~~~

Pharping, Nepal 2006 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

The mountain village of Pharping was my home in Nepal, but in 1997 I also kept a room in a Kathmandu Valley house near Boudha for some months with Tulku Tsultrim and his attendant Sonam Gonpo. One evening, I was alarmed by how ill I felt— dizzy and totally sapped of energy. The following morning, I told Tulku Tsultrim I was not at all well. Both he and Sonam said they would return from puja early to check up on me. However, as they are Tibetan and Tibetans habitually adhere to “lama time,” which means no fixed hour for meeting, I resigned myself to languishing in bed as the afternoon wore on.

Footsteps drew my attention toward the bedroom window; I glimpsed a stranger walking by hurriedly to the inner courtyard of our residence. He knocked loudly at the door, but I was too weak to get up. Later, in the apartment overhead, I heard scuffling noises and a few faint cries as I drifted into a deep sleep. At eleven p.m., I woke to find the house and grounds overrun with police. Our upstairs neighbors had been knifed to death.

My grogginess spared me interrogation by an officer who loomed over the foot of my bed. “Oh she knows nothing,” he declared on rejoining his cop colleagues down the hallway. (I had a sudden flash back to the man who first knocked on our door, then rang our neighbors’ bell.) Furtive as a cat, I slipped into Tulku Tsultrim’s room off the hall. Tulku-la was tucked in bed, hunkered down for the night. I crouched low by his bedside and whispered nervously, “My passport says I’m in India, but as you can see, here I am—in Nepal. What should I do?”* Tulku-la’s eyes widened.

Early the next morning, Tulku Tsultrim directed me to send a fax to Sogyal Rinpoche and Dzogchen Rinpoche, alerting them to the death of our neighbors, a married couple who were dharma jindaks (sponsors) and prominent dzi-stone dealers. (Dzi stones are to Tibetans what diamonds are to Westerners.) I also went in search of new quarters for us. I faxed the messages, booked rooms at the Dragon Guest House, and upon returning walked headlong into a heavy congregation of police in our livingroom.

Dzi stone

“Oh, please,” I said, “Tulku Tsultrim is a precious lama recovering from TB. Kindly be gentle and more respectful.” What could I do to cut through the rude, heated interrogation? The cop abruptly turned his belligerence towards me and said,

“So, Ani-Lahhh... How long have you been in Nepal?”

In that moment, the Vajra Guru blessed my speech: “Oh, I’ve been in Nepal for many, many lifetimes. I love Nepal.”

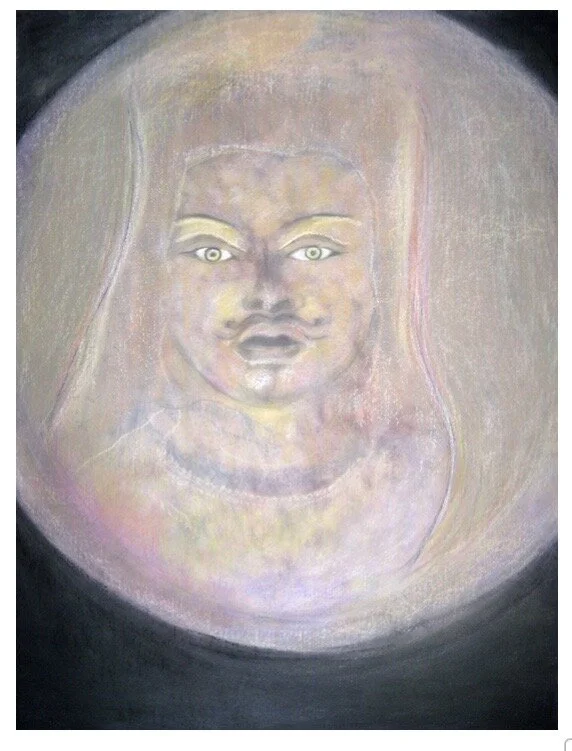

Guru Rinpoche. Drawing by N. L. Drolma (conté crayon, watercolor, pastel, 24”x 30”)

The cop’s aggression melted like an errant ice cube in a hot pitcher of sweet tea. I engaged in a bit of harmless banter and spoke of my first rendezvous with Nepal in 1994. Then I looked at my wrist as if to check the time. I wasn’t wearing a watch. (I wore a wristwatch for only one week back in high school, so looking at my wrist was not a natural reflex.) In that moment surely blessed by the Vajra Guru, I looked squarely at the policeman, and then pointed to my naked wrist. “I’m going to be late. May we continue this conversation tonight or tomorrow morning?”

“Oh, you have to go to puja?” the policeman asked.

“Yes,” I replied emphatically, not missing a beat, so grateful to the cop for giving me my exit line. His query pushed me into high gear. “But first I must prepare a few things,” and I inched backwards into my bedroom. I’m going to puja all right, and I’m not coming back. I couldn’t very well leave for puja with my suitcase and not arouse suspicion, so I crammed whatever essentials would fit into my large western shoulder bag and nun’s jola. (Fearing the cops might confiscate my film and camera, I exposed to the light a roll of photos I took of Dudjom Yangsi in Pharping; I didn’t want to bring the slightest trouble to the precious tulku visiting from Tibet.) Tulku Tsultrim and his attendant, Sonam Gompo joined me at the Dragon Guest House some hours later.

The next morning, Tulku Tsultrim informed me that he was going back to the dzi stone dealers’ house. I begged him not to because word had spread that our residence was quarantined and he surely would be detained by the police. But Tulku Tsultrim was firm in his decision, and Sonam Gompo accompanied him. By late afternoon, I received confirmation by phone that they were under house arrest. (Tulku Tsultrim had returned to the property to conduct the traditional forty-nine days puja for the deceased, but I only learned of this weeks after the fact.)

The tension and drama was unrelenting. The police were calling and leaving messages for me at the guesthouse, requesting that I come down to the police station. Instead, I paid a visit to Tsikey Choling Rinpoche at Ka-Nying Gompa. The Buddhist teachings say how everything is illusion, from A to Z, including the Primordial Buddha. I needed a master’s help to see the illusory nature of my circumstances. I was taking myself and everything else too seriously.

“Serious reaction to phenomena as reality is destructive because it causes energy to be disturbed, diminished, or lost.”

—Thinley Norbu, White Sail

Indeed! I sat in the anteroom of Ka-Nying Gompa in a sweat of fear and gave myself a good talking to. You’re meeting with the incarnation of Terton Chogyur Lingpa. Pull yourself together and sit up straight. The door-curtain parted and I was politely ushered in.

Tsikey Choling Rinpoche, son of Tulku Urgyen, father of Dilgo Khyentse Yangsi (Photographer unknown)

Chokling Rinpoche’s ample, jolly figure was a comforting sight. As I began prostrating to Rinpoche, my face swelled up in a sudden torrent of tears. Rinpoche gestured quickly for assistance; I was offered tea and biscuits—and tissues—as I recounted details of the “Dzi Stone Murder.” Rinpoche asked me a few questions and said how lucky I was, all things considered. Chokling Rinpoche is a vajra master and he was not going to let me indulge too long in the story or in my emotions.

“I’m a very busy man today.” Rinpoche looked at his wristwatch and remarked on the hour. I had no wish to leave the monastery’s shelter, but the interview had taken its natural course. “Do your practice,” was Chokling Rinpoche’s parting counsel.

Meeting with Rinpoche loosened my fixation on the outer circumstances. Instead of seeking a material refuge or help from elsewhere to cut through hope and fear, I mostly kept to myself and sat on my meditation cushion one-pointedly. Police investigators in plainclothes visited me at Dragon Guest House three weeks later. Their questions were perfunctory and friendly. I was now free to return to my mountain retreat in Pharping.