Winging It

~~~~~

“[W]hen the face of loneliness is known to you,

Then you will find the Himalayan hermitage.

The jungle child sings his song

Sad and alone yet weeps for nothing.

And joy is in him as he hears

The flute the peaceful wind is blowing.”

— Chogyam Trungpa

Two camera-shy monks and one high spirited nun in the outer courtyard of Thubten Choling Monastery, Solukhumbu, Nepal. Winter 1996 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

~~~~~~~~

Goat eyeing sitting ducks, Pharping, Nepal (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

In December 1996, not long after ordination in Solukhumbu, I returned to Pharping and found a room to rent in a Nepali household only yards from a feeding ground for three of the world’s largest pigs—and for only twelve US dollars a month. At the high end of the street, just off the center of town, ducks waddled among a few playful goats.

The room sparkled with light and offered views of a garden and village rooftops, but the windows allowed for no screens. At dusk, a variety of colorful bugs usually visited. Most of them didn’t bite. The bugs that made their way across the hall into the shower stall, which had a sealed plastic window, never made it out. Despite this and other quirks, my room was ideal because it was only a five-minute walk to Chatral Rinpoche’s monastery.

The sound of dharma ruled summer evenings in Yangleshö: it was an inspirational cacophony of cymbals, drum, and bells, long base notes of Tibetan horns, and the song of the cuckoo. There was the afternoon din of June bugs too. “Bu puja!” Seymo Saraswati quipped—a fitting term for that haunting ceremonial drone of insects. (Bu means insect, and puja, religious ceremony. Puja is so much a part of the Nepali vernacular that it’s even a brand name for soap.)

HH Chatral Rinpoche’s monastery Rigdzin Drubpe Ghatsal, Yangleshö, Nepal 2006 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

One morning as I was about to leave Chatral Rinpoche’s residence, I spotted Sogyal Rinpoche (flanked by students left and right) walking briskly up the path to the house. I turned on my heels in the vestibule to join Sogyal Rinpoche in Chatral Rinpoche’s chambers. Chatral Rinpoche held up the traditional red protection cord and dangled it before me, asking if I, like the other student visitors, wanted one. Did I need another red cord to feel protected by Rinpoche? Chatral Rinpoche’s playful gesture calmed the jumble of thoughts that had arisen in me at this chance meeting with Sogyal Rinpoche. We received the reading transmission from Chatral Rinpoche for the practice of the Dudjom Tersar “ngondro,” a preliminary practice that is the bedrock for advanced practices. Ngondro is also said to be a complete practice in itself that can enable a yogin to actualize enlightenment in a single lifetime.

Afterwards, I respectfully tagged along with the other students in Sogyal Rinpoche’s wake to a house nearby for tea and requested a moment to speak with him. Rinpoche told the few students present to cover their ears. They were standing in a row like toy soldiers and, in comical unison, dutifully cover their ears.

“Uh, no,” I said softly.

“Okay, two minutes.” Rinpoche barked. “Everyone— out!” In that very moment, I had my answer to the question I wanted to ask of Rinpoche, and Rinpoche confirmed it: “No need to come to Lerab Ling this summer, my dear. There isn’t the support for monastic sangha. Pharping is the best place for you. You come back to Lerab Ling when you can make a contribution and not as you are now.”

Sogyal Rinpoche leading the first three-month retreat at Lerab Ling, Roquerdonde, France 1992 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Sogyal Rinpoche’s cutting of the umbilical cord was a relief in the sense that I now had the official word from the guru. There was to be no going home to the vajrayana training ground of Lerab Ling. The retreats I attended there were vividly ongoing in my mind and primed me well for maturing my practice in Nepal. The bare-boned simplicity of Pharping was guaranteed to cut this New Yorker down to size. A blossoming connection with Chatral Rinpoche would also deepen and refine my understanding of the buddha-dharma. In 1996, I was Sogyal Rinpoche’s first student to take nuns vows, a radical step at the time. Relocating to Pharping was an unequivocal leap of faith, tinged with a wistful sadness, having shed my western cocoon. Lama, you alone know. I was an American caterpillar inching her way on Himalayan soil, determined to one day fly in the sky of wisdom that makes no distinction between East and West.

Caterpillar, Lerab Ling, Roquerdonde, France 1992 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

I had purchased a one-way ticket to Nepal. Although I made a conscientious effort to leave America with all i’s dotted and t’s crossed, it felt more like I just grabbed a toothbrush and left town the way someone might walk out of a faltering marriage—exhausted, harboring no ill feelings, wanting no material settlement, only a fresh start. Living tongue-tied among Tibetans during my initial months in Boudha was maddening, but it was unequivocally delightful to be free of my New York worldly routine.

It was only years later, after traveling occasionally short on rupees and without companion to Sikkim, Hong Kong, and Bhutan that I realized I had pulled the rug out from under my own feet. I was a homebody who had tricked herself into homelessness. To look back and hanker for what might have been made no sense. There were times, however, when I questioned my sanity; the nomadic Spartan lifestyle was not easy. Yet there were many occasions, too, of unalloyed joy, quiet smiles, and appreciation of my minimal wardrobe and living quarters.

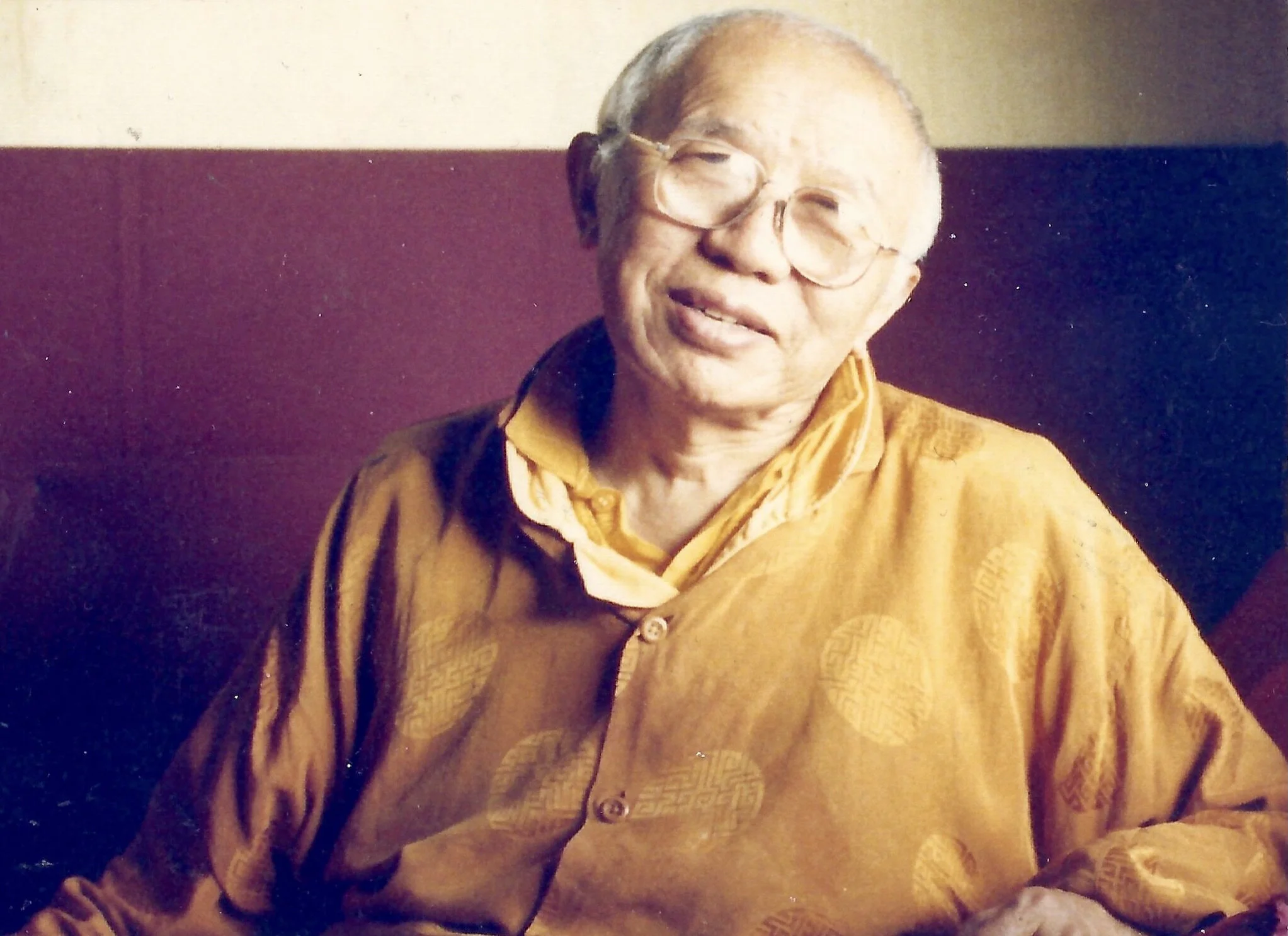

Alak Zenkar Rinpoche, NYC, 1993 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Alak Zenkar Rinpoche had recorded two inspiring audiotapes for me: one in Tibetan of prayers by Jigmé Lingpa, and the other in English of The Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva by Thogmi Zangpo (with lively folk songs of Amdo, Rinpoche’s birthplace, on the flip side). The tape served as a comforting anchor during my first three months in Nepal as I was a foreigner without friends or community. When my high-end Sony stereo cassette recorder was pickpocketed in Kathmandu, and with it the tape of Zangpo’s classic verse, I was despondent for having lost this unique recording of Zenkar Rinpoche’s spoken words. Rinpoche’s precise articulation and the timbre of his voice resonated with the beauty of the text that went far beyond the words themselves:

“Through reliance on a true spiritual friend, one’s faults will fade away/ And good qualities will grow like the waxing moon. /To consider him even more precious than one’s own body is the practice of a bodhisattva.”

The sooner I could let go of my loss, the better. Here was an opportunity to apply the meaning of The Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva to the situation at hand and look on the thief with compassion. Could I do that, or at least rejoice for the thief as he now had a karmic link with Zenkar Rinpoche and the buddha-dharma?

~~~

Calligraphy of The Bodhicitta Prayer courtesy of Kyabje Alak Zenkar Rinpoche:

:

“May bodhicitta, precious and sublime/arise where it has not yet come to be/and where it has arisen may it never wane/but grow and flourish evermore.”

~~~

Several fellow Westerners could not fathom why I was taking nuns vows as a practitioner in the Nyingma tradition when it has been said that no such austerities are necessary for Nyingmapas. The Nyingma tradition is rich with stories of practitioners who became enlightened as householders, and their lives illustrate that monasticism is not requisite for mastery of the Dzogchen teachings. Yet, it is also the case that many Dzogchen masters undertook study, training, and living as a monastic practitioner in their early years, and others late into their lives (e.g., Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö) or throughout (e.g., Khenchen Jigme Phuntsok).

It was my extraordinary good fortune to receive Dzogchen teachings. However, it wasn’t easy for me to trust the simplicity of Dzogchen. It is said that unless a person is of superior faculties, it takes time to deepen one’s understanding and attain unshakable confidence; Dzogchen is utterly profound. Ordination for me, therefore, was not the goal, but unarguably skillful means for sounding the ocean depths of dharma. My aspiration was to abide in timeless pure awareness beyond the keeping or breaking of vows.

Lofty aspiration, however, did not make me immune to comments by practitioners whose attitude toward monastics was patronizing at best. Even more ego-crushing were the vacant looks from Westerners and Tibetans in Boudha who knew me prior to ordination but afterwards failed to acknowledge my “hellos” at first or even second glance, so altered was my physical appearance. A few acquaintances, on recognizing me, actually retreated a few steps. It was difficult for them to relate to the robes and the bald head which blatantly signaled my commitment to spiritual practice.

Recollecting the bias that I myself held during my early years in the dharma makes me wince. Though I briefly entertained the thought of becoming a nun, I habitually screened out information about monasticism; I was caught up in the excitement of having found “my” teacher and “my” path—myopia that often afflicts seekers in the early stages of spiritual inquiry. Monks and nuns were a breed apart, or so I thought, and I was not interested in joining an ascetic religious order. Images of the Middle Ages flitted through my mind: cloistered prayers and confession, the story of Abelard and Heloise, vaulted ceilings, cold bedchamber, and chamber pots. My assumptions about monasticism and its particular role in Tibetan Buddhism remained intact until Zenkar Rinpoche lowered the boom and pushed me in a direction that swept aside cultural stereotypes.

My resolve as a newbie in maroon robes was tested straight away at the Ngakso Drupchen commemorating the parinirvana of the great Dzogchen master Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche.

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche in his room at Nagi Gompa hermitage, Nepal 1994 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

Ka-Nying Gompa was packed with devotees. I came early enough to sit with the ordained, but a few nuns motioned with their hands for me to move and make room for their Tibetan sisters, and they repeatedly shoved me aside. This incivility was no small source of amusement to them, but for me tiresome. I walked away and sat in the rows set aside for the Western practitioners. A translator whose work I much admired insisted I move from my newfound spot, saying that all the space was reserved. Put off by this variation on the children’s game of Musical Chairs, I headed for the exit, then wised-up and let my body sink among the Tibetan pilgrims who were more or less sitting on each other’s laps at the entrance to the crowded gompa. During a break in the puja, as the lamas were making their way out the front entrance, Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche, the monastery’s abbot and eldest son of Tulku Urgyen, spotted me knotted up behind the huge doors.

“Ani-la, I want you sitting with the nuns,” Rinpoche said pointedly. Rinpoche’s words gave me the confidence and adrenaline necessary to take and hold my seat among the robed sangha for the weeklong puja. The temple’s air was thick with blessings. Many great rinpoches were in attendance. When Nyoshul Khen Rinpoche entered the shrine room, happiness suffused every inch of my being; I hadn’t heard that he was in Nepal. Khenpo was led to take his place on a prominent throne directly across from where I was sitting. Ah la la ho!

At a break in the puja, I met with Khenpo’s wife Damcho-la who confirmed for me that Khenpo was ill and not seeing anyone. I made a date for tea with her alone. At the appointed hour, to my surprise, Damcho-la led me straight away to visit Nyoshul Khenpo in the guestroom at Ka-Nying gompa. Khenpo sat upright in bed and motioned for me to come close and not to say much, but just to sit with him. It was a singular blessing and poignant meeting; I sensed it would be our last meeting in this lifetime. Khenpo, every day I see your face.